To the Editor, The Guardian

I know that Simon Jenkins is fundamentally on the same side as I am, and I'm sure it wasn't he who chose to put that offensive phrase in his headline (A banana republic police HQ maybe, but not a home for the Elgin marbles, 23 October). But his piece did contain more than its fair share of anti-Greek prejudice. The Greeks were 'foolish' to turn down the offer of a loan of the Elgin Marbles this summer (a heavily conditional offer, confined to a few pieces, never officially proposed and withdrawn as soon as mooted). They have consigned the excavated ancient site under the new museum to a 'surreal dungeon' (unfair: it is to be open to visitors). And Jenkins cannot have it both ways: if the Greeks previously 'spoiled their case' for restitution of the Marbles by shortcomings in conservation, then he should not be complaining now that the restoration works on the Acropolis are so painstaking.

Anyway, the Greeks have now 'gone to the other extreme' with a building that 'screams the supremacy of Big Modernism' and looks like 'the police headquarters of a banana republic': Bernard Tschumi's New Acropolis Museum in Athens, which is the real target here. Comment is free, and a whole series of other expert architectural critics have commended Tschumi's building for exactly the opposite quality - 'handsome', 'unassuming', 'minimalist', 'unpretentious' - to what Jenkins detects. Simon Jenkins prefers the interior to the exterior: fair enough, so do many of us. But there was no call to package his criticism in this offensive wrapping paper.

Anthony Snodgrass

Chair, British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles

Thursday 22 October 2009, Simon Jenkins for The Guardian

A banana republic police HQ maybe, but not a home for the Elgin marbles

I am a restitutionist – but the new museum fails to clinch the case. It is not so much an argument as a punch in the face.

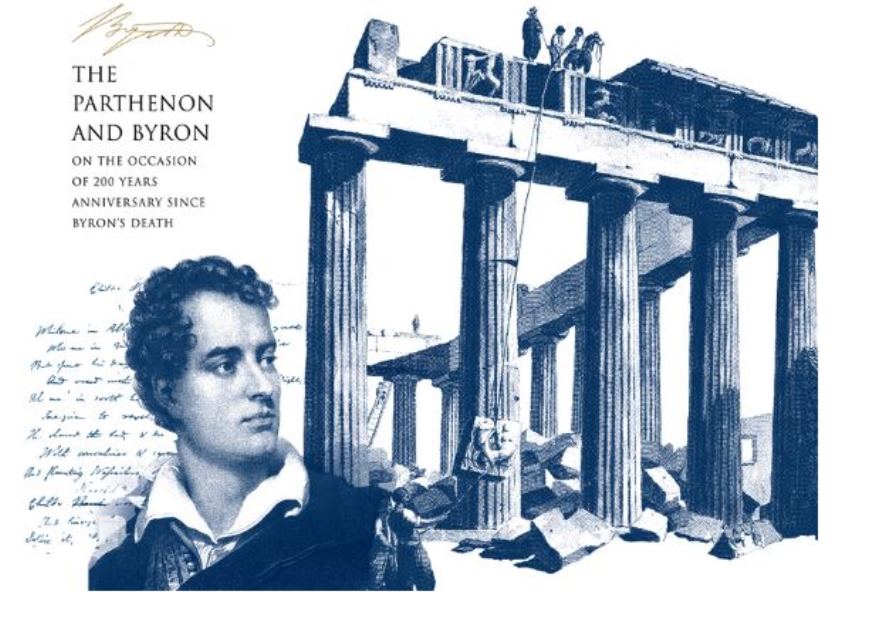

In 1812 Lord Elgin loaded the last of his Acropolis sculptures on to ships in Piraeus and set sail for England. Four years later and bankrupt, he sold them to the British Museum. This summer the Greeks, eager for their return, staged what they hoped would be a definitive retort by opening a £110m museum to house the marbles against the slopes of the same Acropolis. It is the most costly poison-pen letter in the history of cultural exchange.

Any lawyer can prove anything, and I happen to agree with those who regard the Elgin marbles as legally Britain's. But in any meaningful sense, they "belong" in Athens. As 56 of the surviving 94 panels of the Panathenaic procession, they should rejoin the 36 in the new museum. Precedent is not an issue, being the last refuge of reactionaries and those who have lost an argument. The Elgin marbles are, to put it mildly, a special case.

To me, architectural sculpture belongs on the building to which it was once attached. If it cannot be re-attached then it belongs in its climate, culture and context. The restitution of the marbles to Greece was thus always a noble goal of cultural diplomacy. Whenever I visited Athens, I came away ashamed at Britain's insistence that it would never return them, but this was coupled with sadness that the polluted, un-conserved and undistinguished city of Athens seemed determined to undermine its case.

Athens has now cleaned its air and its city. Last week the view of the Acropolis from the adjacent hill of Lycabettus was glorious, with the streets subdued in mist below and the deep blue bay of Phaleron shimmering in the distance. The sunlit slopes of the Acropolis were rid of traffic and immaculately landscaped. Athens seemed on its best behaviour. So was the case for restitution clinched?

I have to admit that, if anything, the case is weakened. When restitution was a futurist fantasy, idealism could rule the day. Sending back the marbles was part of a dream, in which the Parthenon itself might be restored, as the Stoa of Attalus in the agora has been restored. Perhaps the marbles might find their way back on to the temple. Perhaps a museum might be built for the entire frieze, completed with not only Elgin's panels, but missing ones conjectured from the original Pantelic quarries. Perhaps they might be repainted.

Today we can see what restitution would mean in practice. The argument has been hijacked by the gods of modern museology. Just as previously the Greeks spoiled their case by their conservation shortcomings, now they have gone to the other extreme and put their cause in the hands of archaeologists and architects – stripping it of all passion.

The new museum, designed in pastiche Corbusian style by the Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, is not so much an argument as a punch in the face. It is big and brutal, like something flown in overnight from Chicago. Its rear hits the street with two storeys of concrete and corrugated metal, set back from the road like the police headquarters of a banana republic. The giant entrance porch cantilevers out towards the Acropolis, screaming the supremacy of Big Modernism over the serene stones of the Acropolis opposite. It is the worst case of architectural egotism, of I can do anything bigger than you.

As if to slam the point home, the excavated streets of old Athens, discovered below, have not been laid out as a public site but consigned to a surreal dungeon beneath the concrete columns and glass pavement of the museum's ground floor. Were this Pompeii, no one would have dared such an outrage. Where there should be elegance and deference, there is all the architecture money could buy.

The foyer is in the air-terminal style beloved of big-time museums – witness the Louvre, Tate Modern or New York's Museum of Modern Art. The first two floors offer a mass of structural space for little content, though the oppression is relieved by the exquisite delicacy of the classical sculptures.

These objects – ethereal maidens with plaited hair, beautifully carved boys, the caryatids of the Erechtheion, a mischievous Silenus – seem to float before the viewer, most of them free of glass and deliciously close to the eye. They suggest that Athens has treasures aplenty, without having to reclaim those lost to other cities. (Indeed, the city's new gallery of Cycladic art is one of the finest archaeological museums I know.)

The museum's undoubted coup, political as much as sculptural, is the top gallery, dedicated to the Parthenon. Fashioned as a pavilion with a surrounding colonnade, its walls are hung with the frieze panels still in Greek hands. Glassed on all four sides, the terraces look out over the roofs of Athens and to the Acropolis above. Here the absence of the London panels is undeniably painful. Their replication with plaster casts makes some amends, but the absence of the end pediments is particularly sad. The political point is made, the visual impact stunning.

While the Greeks win full marks for theatricality, the gallery is not the Parthenon, nor a copy, nor remotely deferential to the original. Architecture and museum technology have combined to dictate a lowering ceiling and heavy steel and concrete frames, overlooked by lighting gantries, window blinds and double glazing.

The whole thing is unremittingly hi-tech, with Tschumi determined to push himself forward as a rival to the builders of the Acropolis. The result is ironic. I find the British Museum's bland and gloomy presentation of the marbles somehow more pristine than these souls lost in a modernist wilderness.

Again I would be more sympathetic to Athens were it not for the continued chaos of the Acropolis itself. In a lifetime of visits, I have never seen it free of builders' yards, now more than ever. It was taken from world view by the archaeological profession in the 1980s and submitted to a protracted torture of poles, planks, cranes, rails and sheds. It seems destined to last for ever. I doubt if readers of this article will be able to photograph the Acropolis free of scaffolding in their lifetimes: I have not.

With the Propylaia also covered in scaffolding and the Erechtheion a half-rebuilt "designer ruin", the Acropolis composition is a monument not to ancient Athens but to the unknown 20th-century archaeologist. It is shocking, as if London were to keep St Paul's and Big Ben in scaffolding in perpetuity.

The squabble has now become messy. The Greeks were foolish this summer to reject the British Museum's half-mooted offer to loan the Elgin marbles back for the opening, on the grounds that acceptance might concede London's title. The Greek point would have been better made had the world seen the marbles united, however briefly, than by this legal nicety.

If I were seeking a compromise, I would return the pediments, which are the most glaring omission from the new museum. I would also return Elgin's filched Erechtheion caryatid. As for the rest of London's hoard, I remain a restitutionist, but less convinced than before. Athens has substituted a bunker for a dream and failed to end the argument.