“Any holders of Parthenon Sculptures outside Greece to return them forthwith to Athens, where they can be reunited with their brothers and sisters”, the distinguished historian of the University of Cambridge, Dr. Paul Cartledge, stated in Kathimerini. Vice-Chairman of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles and a 50-year scholar of ancient Greek history, he congratulates the tireless struggle of the Greeks for the return of their stolen antiquities, while stressing the favourable climate in the UK for the reunification of the Parthenon Marbles.

“YouGov polls regularly register above 60 percent support for reunification” argues Professor Cartledge, explaining that “The UK’s main journal of record, The Times, has recently flipped its longstanding editorial policy – from a retentionist to a reunificatory stance”.

Regarding the problems of the sculptures' storage at the British Museum, Cartledge, critical of the British Museum, also stresses their poor conservation, focusing among other things on the issue of dampness in Room 18, as well as the series of thefts by the former curator of the Greek and Roman wings. According to Dr. Cartledge, «The Museum’s repeated claim to have been an exemplary caretaker of ‘its’ Marbles since 1817 has also been exploded on two academic fronts: a) by the late William St Clair, exposing the hushed-up, irreparable damage (‘skinning’) inflicted on frieze sculptures on Lord Duveen’s orders in the late 1930s; and lately b) by international human rights lawyer Professor Catharine Titi exposing the fragility of the UK’s original claim to legality of purchase in 1816”.

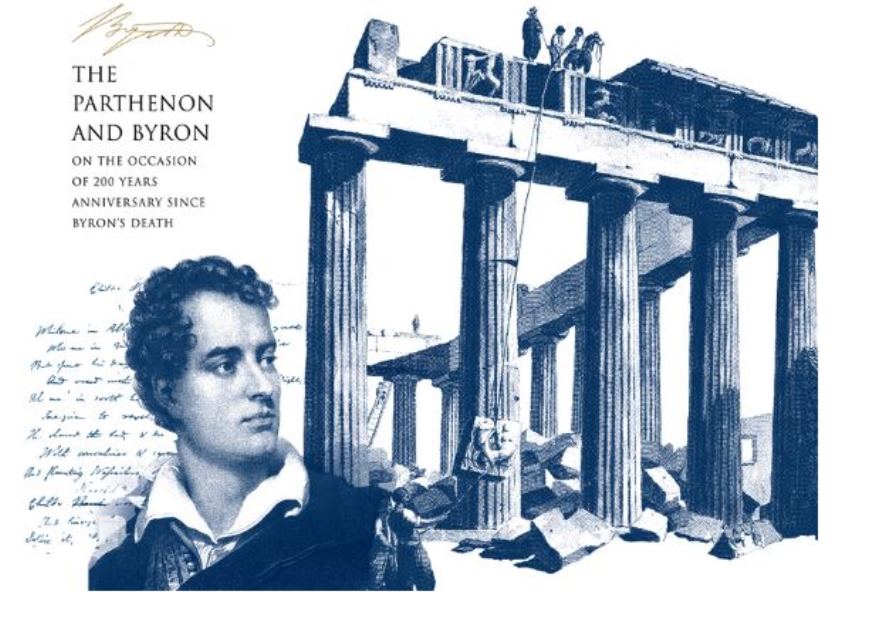

The timeline of the sale of the sculptures is set four years after the removal of the sculptures from the Acropolis, but personal debts lead Lord Elgin to submit a proposal to the British Museum to sell the stolen sculptures, estimating their value at £35,000, with the British Parliament accepting Elgin's offer. From then on, the sculptures began to be exhibited at the British Museum with the newly-established Greek state making the first request for their return in 1835.

But did Lord Elgin have the right to sell the sculptures? According to Dr. Cartledge, who relies on the legal assumptions presented in the book, “The Parthenon Marbles and International Law”, “the UK does have legal title to ‘ownership’ of the British Museum holdings, but only with regards to domestic law. Contrariwise it is evidenced that Lord Elgin’s title to what he sold to the U.K. for £35,000 in 1816 was anything but Acropolis rock-solid. So far, despite rigorous searches in Ottoman archives, the best that ‘retentionist’ defenders of the UK and the BM can dredge up is an Italian translation of a permit issued by an Ottoman high-up, not formally carrying the imprimatur of the Sultan himself, allowing Elgin’s men to pick up marbles lying around on the ground and copy stones bearing figures – no mention of hacking worked marbles off the extant Temple itself and having them shipped at great risk of further damage to the UK”.

“Conclusively, one of the issues at the heart of that ancient-history debate is the existence or nonexistence of any sort of official Ottoman firman authorizing Elgin and his cohorts to damage the Acropolis. On the other hand,”, Professor Cartledge adds, “the reunification requires at least one, possibly two Acts of Parliament to be either amended or rescinded: a) of “1816” about the purchasing of and the claim to ownership of the Elgin Collection including the Parthenon Sculptures and, b) of “1963”, “Museums Act”. That requires parliamentary time and support. The present (Tory) UK government is dead against even talking about any legislative change, for example, witness the UK PM’s recent extreme discourtesy to the Greek PM. The Chair of the British Museum Trustees is, therefore, unable to help the Greek government directly, even if he wanted to; his talk about a ‘deal’ is just that – “hot air”.

After two centuries of claims by the Greek State, the provocative fashion show in the Duveen Hall, in front of the Greek antiquities, provoked the anger of the Greek Ministry of Culture, with the Minister of Culture Lina Mendoni speaking of "zero respect", while the British media reiterated the conflict between the two governments and the Greek demand for the return of the sculptures.

As vice-chairman of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, Professor Cartledge argues for the reunification of the sculptures on Greek soil, stressing, “Outside Athens and Greece any Parthenon Marbles held abroad risk looking like imperial loot without much if any current cultural-political significance”. At the same time, he underlines, “The Parthenon was a temple of as well as on the Acropolis, so any sculptures therefrom that survive but cannot be re-placed on what remains of the temple itself should be reunited in the dedicated Acropolis Museum”.

Highlighting the historical and cultural value of the Parthenon, the distinguished academic elaborates on the argument of return by explaining that, “due to a series of historic conjunctions, like the liberation of the new state of Greece from the Ottoman empire, end of the Ottoman empire, growth of representative democracy, the increased importance of the Parthenon as a symbol of the world’s first democracy or ‘people-power’, division of Europe – and the world - between democracies and autocracies, Parthenon stands as a symbol of both cultural excellence and political freedoms, and even more importantly so. Therefore”, he adds, “any holders of Parthenon Marbles/Sculptures outside Greece to return them forthwith to Athens, where they can be reunited with their brothers and sisters in a fully appropriate space”.

In summary, the Emeritus Professor of Cambridge argues that the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Greece will influence the global debate on the return of stolen antiquities to their place of origin, pointing out that, “The Parthenon Marbles is, in fact, a unique case, without implications for the fate of any other ‘restitution’ case, but, even so, reunifying the Parthenon Marbles back in Athens would have a mega impact on other legitimate claims for repatriation currently being lodged against the British Museum, above all perhaps that for the Benin Bronzes”.

This article was first published in ekathimerini and writte by Athanasios Katsikidis.

To read the article in Greek, follow the link here.

Comments powered by CComment