Q&A: Safeguarding the world's ancient treasures

Preserving Roman antiquities comes at a high cost

Old and new at the Acropolis Museum in Greece

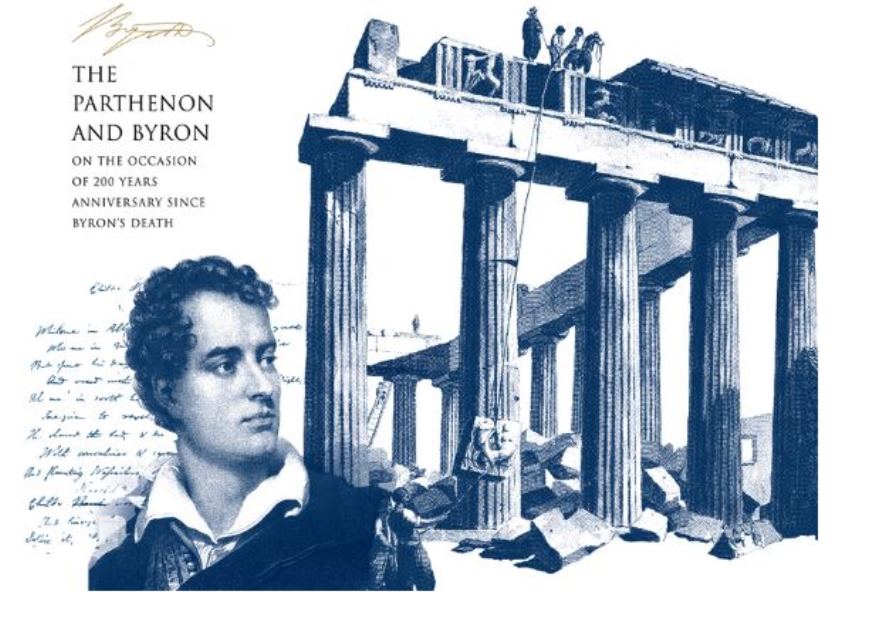

Greeks lobby for return of Parthenon marbles to Athens

Do Greece's ancient treasures belong in London?

This week, Worldfocus aired a report by special correspondent Lynn Sherr and producer Megan Thompson exploring the new Acropolis museum in Athens and the controversy over the appropriate home for the many Parthenon sculptures currently housed in the British Museum in London.

The marble artworks were acquired by British ambassador Lord Elgin in 1816 for 35,000 pounds. Many Greeks think that the pieces, which came to be known as the Elgin marbles in Britain, should be returned to Athens.

Earlier this year, Lord Elgin's great-great-great-grandson Alastair Bruce defended his actions in a blog posted on Sky News:

[Elgin] was passionate about antiquities and wanted to preserve them from the destruction they faced, at a time when war and local indifference was grinding away at the edifice.

But the process broke him and he was forced to sell them to the Government in 1816. They were put into the British Museum and have been there ever since – owned by us all, in trust for the world....

If Britain repatriates the Elgin Marbles, it will not be long before every country in the world puts in claims for items displayed in the British Museum to be returned. Museums in London, New York and elsewhere might face a mass repatriation from the precedent.

For more on this topic, we spoke to Cindy Ho, the president of S.A.F.E. (Saving Antiquities for Everyone), an advocacy organization that works to combat looting and smuggling of the world's antiquities.

Cindy Ho: Thank you for the opportunity to speak on Worldfocus. First of all, I would like to mention that I choose to refer to the sculptures from the Athenian acropolis now at the British Museum as the Parthenon sculptures, or sculptures of the Parthenon. While the debate over the legality and propriety of Lord Elgin's acquisition continues nearly two centuries later, it is perhaps better not to name these important artifacts after the person who took them, particularly when that person's name, the term "elginism," has entered the vocabulary as a synonym for "cultural vandalism."

As an organization, SAFE has no official position on the restitution of the Parthenon sculptures. Rather, our position on the matter centers on the issue of context, and the loss of information when a looted object is ripped out of the ground.

I personally believe that the Parthenon sculptures belong in their place of origin: The Parthenon, in Athens.

Worldfocus: Are [the marbles] symbols of a larger issue?

Cindy Ho: Yes, elginism is synonymous with cultural vandalism — it refers in a general to the appropriation of another nation's cultural property as one's own. Whether the Parthenon sculptures should, or should not, be returned to Greece has dominated the debate over who owns cultural heritage. But the question of ownership and legality is, for SAFE, only part of the picture. Whether Lord Elgin had the proper permission to remove the sculptures from Greece 200 years ago may remain unresolved. Perhaps we need to look at that situation in a historical context of rampant colonialism. While what Lord Elgin did may be considered plunder by many, SAFE focuses on plunder of a different nature: The ongoing looting of ancient sites to feed the multi-billion dollar illicit antiquities trade. Looting robs us of knowledge that the past can impart. Objects ripped out of the ground without proper documentation leave us voids of information that can never be filled. No paperwork can ever replace this loss.

Antiquities, monuments and archaeological sites are the precious witnesses to ancient cultural history. Objects uncovered in their original contexts, properly interpreted, provide insight into the way our ancestors lived, their societies and their environments. They complete our view of ancient life and enrich our understanding on many levels. As such, antiquities comprise an essential part of our global cultural heritage.

This physical fabric of the past is vital to the moral and spiritual fabric of the present and future.

Worldfocus: But isn't it impossible to return every object to its native country? Wouldn't that empty the great museums of the world?

Cindy Ho: SAFE does not favor or call for large-scale repatriation. National and international laws and treaties are in place to protect cultural heritage and property SAFE believes in abiding by these legal mechanisms. Therefore, if the acquisition or importation of any object in recent times violates one of these laws (such as the National Stolen Property Act in the U.S.) or treaties (such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention), and its native country makes a proper request for the return of an object, then all legal means should be applied to return that property to its rightful owner, whether it be a citizen in a foreign country or a nation that claims ownership of all archaeological material found on its soil. If we simply followed the laws that already exist, all parties will benefit, and the great museums of the world will not be emptied of their treasures.

Worldfocus: What if the home country simply cannot afford to maintain all of the antiquities in is possession?

Cindy Ho: There are other reasons why a home country is not always in the position to maintain all of its antiquities, aside from financial difficulties. For example, a country at war, such as Iraq, may not in the best position right now to protect its cultural property. The solution calls for international cooperation and assistance. Objects can be on loan to museums in other nations while situations in home countries improve. Long-term loans have worked and should continue to do so. This would benefit museum-goers as well. But cooperation and sharing will need to depend on the quality of relationships between nations and their cultural institutions. This argument that if the museums of poor nations (usually culturally rich) are not up to standards (usually set by nations financially rich but culturally less so) then antiquities should be protected in better-equipped facilities in richer nations has been used against Greece's case for the return of the Parthenon sculptures. With the newly constructed Acropolis Museum, this argument does not work anymore.

Worldfocus: Which countries are in greatest danger of losing their ancient heritage and why?

Cindy Ho: Countries which have not already been "looted out," such as those in South America, Africa, and parts of Asia, are in great danger of losing their ancient heritage. But let's not ignore the fact that right here in the United States, looting is a huge problem. "An estimated 80 percent of the ancient archaeological sites in the United States have been plundered or robbed by shovel-toting looters," according to a 2006 report in The Arizona Republic.

As long as looting persists and the demand for antiquities driven by a huge appetite for the exotic and beautiful is left unchecked, all of our shared ancient heritage is in danger.

Comments powered by CComment