18 December 2021, TA NEA, Yannis Andritsopoulos, London Correspondent for the Greek daily newspaper

Boris Johnson as student in 1986 wrote that the Parthenon Marbles were pillaged and should be returned to Greece. A position the British PM has recently rejected when Greece requests the reunification of these antiquities, and insisting they were 'legally acquired'.

Boris Johnson’s insistence as Prime Minister that the Parthenon Marbles were legally acquired by Lord Elgin and should remain in the British Museum is a complete reversal of the position he previously held, Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea can exclusively reveal.

In fact, as a university student, Johnson urged the British government to return the artefacts to Greece, arguing that they had been unlawfully removed from the ancient temple in Athens.

It is the first time evidence has emerged that the British Prime Minister advocated the reunification of the 2,500-year-old sculptures, a request he has repeatedly rejected publicly in recent years.

In an article written in April 1986 for the Oxford Union’s magazine, Johnson, then an undergraduate at Oxford University, accused Lord Elgin of ‘wholesale pillage’ of the Parthenon.

As British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Elgin removed the sculptures from the Parthenon in the early 19th century, when Greece was under Ottoman rule. He then sold them to the British government which passed them on to the British Museum in 1817.

Writing as president of the Oxford Union 35 years ago, Johnson claimed in his article that an Act of Parliament to hand the Marbles back “could be passed in an afternoon.”

The future Prime Minister went on to accuse the British government of ‘sophistry and intransigence’, saying that Whitehall’s claim that the ‘transaction had been conducted with the recognised legitimate authorities of the time’ is “invalid”.

“A letter from Elgin of 1811 reveals that the Turkish authorities denied ‘that the persons who had sold those marbles to him had any right to dispose of them’,” Johnson wrote.

He added that Elgin “secured from the Sultan a firman to remove 'qualche pezzi di pietra’ - a few pieces of stone - that happened to be lying about on the Acropolis. Elgin's interpretation of this phrase was liberal to say the least.”

This statement contradicts Johnson’s recent remarks regarding the legality of Elgin’s actions. In an exclusive interviewwith Ta Nea published in March, the British Prime Minister claimed that the Parthenon Marbles “were legally acquired by Lord Elgin under the appropriate laws of the time and have been legally owned by the British Museum’s Trustees since their acquisition.” He stressed that this view is “the UK Government’s firm longstanding position on the sculptures”.

“It seems that Boris Johnson was aware of concrete evidence that Lord Elgin’s actions were unlawful from as early as 1986. This begs the question: did he mislead the public when he recently claimed that the sculptures were legally acquired by Elgin?”, a Greek official told Ta Nea.

It is the first time since its publication in 1986 that this article has been made public.

The Daily Telegraph reported last month that Johnson “wrote an article for a student magazine arguing that (the Marbles) should stay here”. In actual fact, though, it is now clear that he argued the exact opposite.

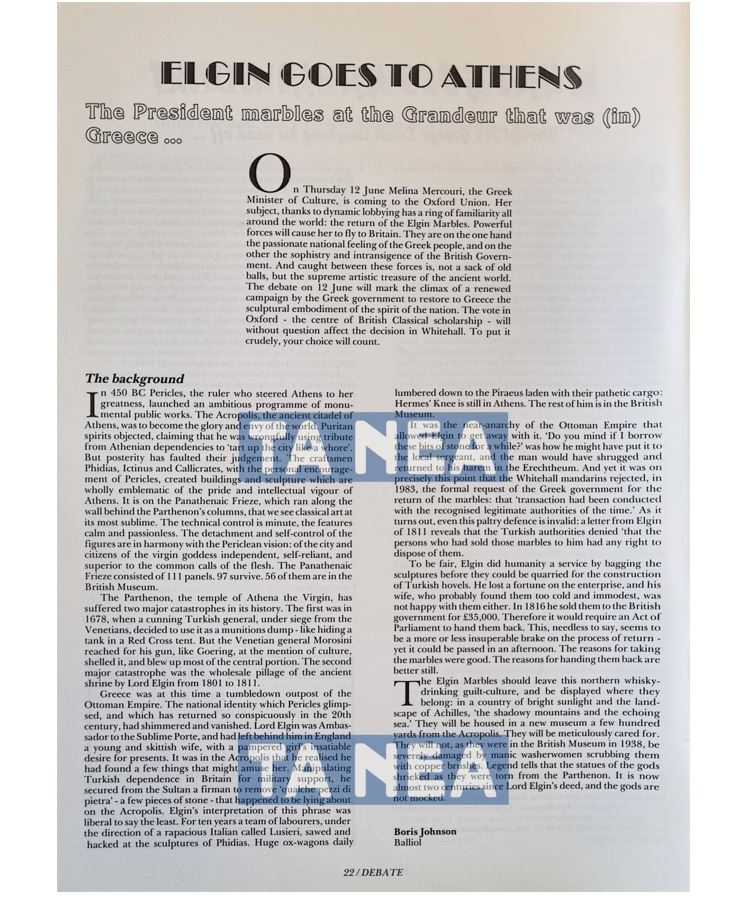

Titled “Elgin goes to Athens – The President marbles at the Grandeur that was (in) Greece …,” the 978-word article was published in Debate, the official magazine of the Oxford Union Society (Vol. 1, No. 3, Trinity Term 1986, p. 22).

Ta Nea found the an unknown article in an Oxford library last week. It is not available online, nor is there any reference to it in the press or on the Internet. Two Oxford sources confirmed its authenticity.

Greece has repeatedly called for the return of the Parthenon Marbles, arguing that Lord Elgin had not secured permission to remove them from the ancient temple. Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Culture Minister Lina Mendoni have said that the sculptures were 'stolen'. In his 1986 article, Mr Johnson appears to accept that view.

However, when he met with his Greek counterpart in Downing Street last month, the British leader rebuffed Mitsotakis’s request for the Marbles to be returned. He claimed that the issue was "one for the trustees of the British Museum".

This is inconsistent with the view he expressed in his 1986 article, in which he said that it is for the British Parliament to decide the Marbles’ fate.

“In 1816 (Elgin) sold them to the British government for £35,000. Therefore, it would require an Act of Parliament to hand them back. This, needless to say, seems to be a more or less insuperable brake on the process of return - yet it could be passed in an afternoon,” Johnson, who graduated from Balliol College with a BA in Classics, wrote.

The sculptures held in the British Museum make up about half of the 160-metre frieze which adorned the Parthenon, a 5th century BC architectural masterpiece. Most of the other surviving sculptures (around 50 metres) are in Athens.

Britain has repeatedly rejected Greece's request to hold talks on returning the Marbles. Earlier this year, a UNESCO committee said that Greece’s request for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures is “legitimate and rightful,” stressing that “the case has an intergovernmental character and, therefore, the obligation to return the Parthenon Sculptures lies squarely on the UK Government”. It also called on Britain “to reconsider its stand and proceed to a bona fide dialogue with Greece on the matter”.

In his magazine article, Johnson, then 21, called on the UK to return Phidias’s masterpieces to Greece so that they can be “displayed where they belong”.

“The reasons for taking the marbles were good. The reasons for handing them back are better still,” the future Prime Minister and Tory leader stressed.

“They will be housed in a new museum a few hundred yards from the Acropolis. They will be meticulously cared for. They will not, as they were in the British Museum in 1938, be severely damaged by manic washerwomen scrubbing them with copper brushes,” he wrote.

It had been claimed that as a student Johnson was "sympathetic" to the Greek request, but no evidence to support this had been presented until now. All his past public comments express the view that the Marbles should stay in the UK.

In 2014, he criticised George Clooney for suggesting Britain should return the Parthenon marbles to Greece. Johnson said at the time the actor needed his “marbles” restored, claiming Clooney was “advocating nothing less than the Hitlerian agenda for London's cultural treasures”.

In a 2012 letter shared with the Guardiannewspaper, Johnson, then mayor of London, wrote that “in an ideal world, it is of course true that the Parthenon marbles would never have been removed from the Acropolis,” but concluded that if the sculptures were removed from London, it would amount to “grievous and irremediable loss”. Therefore, he added, “I feel that on balance I must defend the interests of London.”

In March, the Prime Minister posed for Ta Nea in his parliamentary office next to a plaster cast bust of his “personal hero”, Pericles. The Athenian statesman is credited with ordering the design and construction of the Parthenon from which Elgin took the marbles.

As president of the Oxford Union, Johnson invited the then Greek Culture Minister Melina Mercouri to participate in a June 1986 debate titled: “[This House believes] that the Elgin Marbles must be returned to Athens.” She won the vote.

The Greek government says that the sculptures were illegally removed during the Ottoman occupation of Greece in the early 1800s.

It seems Greece has found an unlikely ally in its quest to reunite the Marbles in the form of the 21-year-old Johnson, who thought that “the Elgin Marbles should leave this northern whisky-drinking guilt-culture” and be displayed “where they belong: in a country of bright sunlight and the landscape of Achilles, 'the shadowy mountains and the echoing sea'.”

Boris Johnson’s article in full:

Elgin goes to Athens

The President marbles at the Grandeur that was (in) Greece …

On Thursday 12 June Melina Mercouri, the Greek Minister of Culture, is coming to the Oxford Union. Her subject, thanks to dynamic lobbying has a ring of familiarity all around the world: the return of the Elgin Marbles. Powerful forces will cause her to fly to Britain. They are on the one hand the passionate national feeling of the Greek people, and on the other the sophistry and intransigence of the British Government. And caught between these forces is, not a sack of old balls, but the supreme artistic treasure of the ancient world. The debate on 12 June will mark the climax of a renewed campaign by the Greek government to restore to Greece the sculptural embodiment of the spirit of the nation. The vote in Oxford - the centre of British Classical scholarship - will without question affect the decision in Whitehall. To put it crudely, your choice will count.

The background

In 450 BC Pericles, the ruler who steered Athens to her greatness, launched an ambitious programme of monumental public works. The Acropolis, the ancient citadel of Athens, was to become the glory and envy of the world. Puritan spirits objected, claiming that he was wrongfully using tribute from Athenian dependencies to ‘tart up the city like a whore'. But posterity has faulted their judgement. The craftsmen Phidias, Ictinus and Callicrates, with the personal encouragement of Pericles, created buildings and sculpture which are wholly emblematic of the pride and intellectual vigour of Athens. It is on the Panathenaic frieze, which ran along the wall behind the Parthenon's columns, that we see classical art at its most sublime. The technical control is minute, the features calm and passionless. The detachment and self-control of the figures are in harmony with the Periclean vision: of the city and citizens of the virgin goddess independent, self-reliant, and superior to the common calls of the flesh. The Panathenaic Frieze consisted of 111 panels. 97 survive. 56 of them are in the British Museum.

The Parthenon, the temple of Athena the Virgin, has suffered two major catastrophes in its history. The first was in 1678, when a cunning Turkish general, under siege from the Venetians, decided to use it as a munitions dump - like hiding a tank in a Red Cross tent. But the Venetian general Morosini reached for his gun, like Goering, at the mention of culture, shelled it, and blew up most of the central portion. The second major catastrophe was the wholesale pillage of the ancient shrine by Lord Elgin from 1801 to 1811.

Greece was at this time a tumbledown outpost of the Ottoman Empire. The national identity which Pericles glimpsed, and which has returned so conspicuously in the 20th century, had shimmered and vanished. Lord Elgin was Ambassador to the Sublime Porte, and had left behind him in England a young and skittish wife, with a pampered girl's insatiable desire for presents. It was in the Acropolis that he realised he had found a few things that might amuse here. Manipulating Turkish dependence in Britain for military support, he secured from the Sultan a firman to remove 'qualche pezzi di pietra’ - a few pieces of stone - that happened to be lying about on the Acropolis. Elgin's interpretation of this phrase was liberal to say the least. For ten years a team of labourers, under the direction of a rapacious Italian called Lusieri, sawed and hacked at the sculptures of Phidias. Huge ox-wagons daily lumbered down to the Piraeus laden with their pathetic cargo: Hermes’ Knee is still in Athens. The rest of him is in the British Museum.

It was the near-anarchy of the Ottoman Empire that allowed Elgin to get away with it. ‘Do you mind if I borrow these bits of stone for a while?’ was how he might have put it to the local sergeant, and the man would have shrugged and returned to his harem in the Erechtheum. And yet it was on precisely this point that the Whiteheall mandarins rejected, in 1983, the formal request of the Greek government for the return of the marbles: that ‘transaction had been conducted with the recognised legitimate authorities of the time.’ As it turns out, even this paltry defence is invalid: a letter from Elgin of 1811 reveals that the Turkish authorities denied ‘that the persons who had sold those marbles to him had any right to dispose of them.’

To be fair, Elgin did humanity a service by bagging the sculptures before they could be quarried for the construction of Turkish hovels. He lost a fortune on the enterprise, and his wife, who probably found them too cold and immodest, was not happy with them either. In 1816 he sold them to the British government for £35,000. Therefore it would require an Act of Parliament to hand them back. This, needless to say, seems to be a more or less insuperable brake on the process of return - yet it could be passed in an afternoon. The reasons for taking the marbles were good. The reasons for handing them back are better still.

The Elgin Marbles should leave this northern whisky-drinking guilt-culture, and be displayed where they belong: in a country of bright sunlight and the landscape of Achilles, 'the shadowy mountains and the echoing sea'. They will be housed in a new museum a few hundred yards from the Acropolis. They will be meticulously cared for. They will not, as they were in the British Museum in 1938, be severely damaged by manic washerwomen scrubbing them with copper brushes. Legend tells that the statues of the gods shrieked as they were torn from the Parthenon. It is now almost two centuries since Lord Elgin's deed, and the gods are not mocked.

Boris Johnson

Balliol

1986

Guardian 18 December 2021

Helena Smith writes: 'The extent of Boris Johnson’s U-turn on the Parthenon marbles has been laid bare in a 1986 article unearthed in an Oxford library in which the then classics student argued passionately for their return to Athens.

Deploying language that would make campaigners proud, Johnson not only believed the fifth century BC antiquities should be displayed “where they belong”, but deplored how they had been “sawed and hacked” from the magisterial edifice they once adorned.

“The Elgin marbles should leave this northern whisky-drinking guilt-culture, and be displayed where they belong: in a country of bright sunshine and the landscape of Achilles, ‘the shadowy mountains and the echoing sea,’” he wrote in the article, republished by the Greek daily, Ta Nea, on Saturday.'

To read the article in full, follow the link here

Telegraph 18 December 2021

Steve Bird also took up the story: 'Thirty-five years ago, Johnson wrote how the UK’s claim to the artefacts relied on the “invalid” suggestion that Elgin had received the approval to remove them from “the legitimate authorities of the time”.

Johnson wrote: “As it turns out, even this paltry defence is invalid: a letter from Elgin of 1811 reveals that the Turkish authorities denied ‘that the persons who had sold those marbles to him had any right to dispose of them.’”

Greece has repeatedly insisted that because the Ottomans were an occupying force in Greece they had no right to sanction the removal of the frieze to anyone.

To read the Telgraph article, follow the link here(there is a paywall).