Delivered at the IARPS Conference, 16 September 2022, in the Pandremalis Auditorium of the Acropolis Museum

Paul Cartledge, Vice-President, of BCRPM & IARPS

‘Just how democratic (in what ways, to what extent) was the (original) Parthenon?’

[Thanks: to Culture Minister Mendoni, to Acropolis Museum Director Stampolidis, to everyone else involved in the organisation of this great conference, and to you, my audience, but above all to Prof. Kris Tytgat, Chair, IARPS.]

‘Ten Things’

It’s often said that the Parthenon – not its original ancient name – is a democratic building, a symbol of ancient Athenian democracy, even a symbol of world democracy. So I thought it might be an idea to dial down the rhetoric (good ancient Greek word!), and to re-examine what exactly democracy meant in Classical Athens in the middle of the 5th century BC/E, and how exactly the Parthenon fitted into that uniquely original political project.

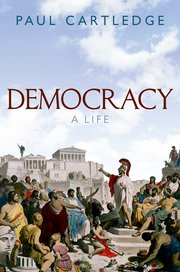

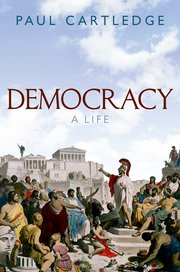

I’ve a little skin in this game of scholarship: in 2016 I published on both sides of the Atlantic a book entitled Democracy: A Life; and two years later, in 2018, the book was re-published in a cheaper, paperback version, but with a crucial addition – an Afterword: in which I traced a brief account of the startling events that had occurred between 2016 and 2018, affecting – sometimes seriously badly - the nature and course of democracy in the contemporary world, again on both sides of the Atlantic (with special reference to the Brexit referendum vote in the UK, the election of President Trump in the US, and the election of Président Macron in France).

My first slide says ‘ten things’, but there are of course many more things than ten that people ought to know about ancient Greek democracy – or rather, since there were many more kinds than just the one – democracies in ancient Greece. But the first and biggest thing of all is this: that no version of democracy in ancient Greece was anything much like any version of ‘democracy’ currently on offer in Europe, the Americas, Australasia or anywhere else in the world today. For this basic, categorical reason: all ancient democracies were direct – the demos, the people, ruled for and by themselves – whereas all modern democracies are representative, indirect, in which the people chooses others – representatives – to rule for them, that is, both in their interest (they hope) and, no less relevantly, instead of them.

As the jacket-image of my Democracy book perfectly illustrates. Of course, it’s not a photo of a meeting of the ancient Athenians’ Assembly (ekklesia) being held on the Pnyx hill below the Acropolis and being addressed by a helmeted Pericles. It’s the idealised vision of a German painter working in the 1840s, within a decade or so of the foundation of the modern Greek state – which looked back to ancient Greece and especially to ancient Athens for validation as well as inspiration. But it was painted when Greece was formally a monarchy, not even a republic let alone any form of modern democracy!

So, how different was the ancient Athenian democracy of Pericles’s time from anything we might recognise as ‘democracy’ today? Let me count the ways!

I’m going to use the text and image of the decree/law shown on this slide as my way in. But first, a word of chronological warning. This decree and this stone date from 336 BC/E, that is, over a hundred years after the Parthenon was first commissioned, in 448/7. And between 448 and 336 a lot of water had flowed under several bridges, so far as democracy at Athens was concerned. In 411 in the midst of a long, expensive and bloody war – with Sparta, then aided by Persian money – the Athenian democracy had been overthrown in a reactionary and violent rightwing coup and replaced with a narrow oligarchy. That narrow oligarchy had lasted only a few months and was replaced with a broader oligarchy, which in turn lasted only 8 months or so, so that by the summer of 410 Athens had regained the democracy it had in 448 (and had had since about 460). Only to lose it again, together with the war itself, in 404, after which Sparta imposed an even narrower and nastier oligarchy, a junta of just 30 ultra-oligarchs. They proceeded to rule very violently, murderously, aided by a Spartan garrison on the acropolis, so violently and so controversially that after only a year even Sparta stood aside when a democratic Resistance defeated the forces of the junta in the Peiraieus, and from 403 Athens was a democracy again.

But not the same democracy again: a new, different and in some ways more moderate or less extreme democracy, one that was moderate enough not to provoke the Athenian ultra-oligarchs into attempting another coup, and one which lasted some 80 years until it was forcibly exterminated by the new Macedonian rulers of Greece, in 322. The document of democracy on your screen belongs to this final phase of democracy, to a very late stage of it, by when the Athenians had been heavily defeated in battle by the Macedonians (Chaeronea, 338), their Theban allies had had their democracy suppressed and a Macedonian garrison installed on the acropolis of Thebes, and the majority of – democratic – Athenian citizens feared that the same fate was about to be imposed on them. Whereupon they passed the Law proposed by Eucrates, a law specifically against not oligarchy but against Tyranny. Here’s a key clause (I paraphrase): If any Athenian should suspect another of trying to bring about the replacement of democracy with a one-man dictatorship, then he might lawfully kill such a traitor without incurring the punishment for culpable homicide.

Why was it against Tyranny? For two main reasons: first, the imposition of a tame local, pro-Macedonian tyrant was how Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander, liked to rule the subordinated, formerly free cities of mainland Greece; second, the Athenians’ own democratic mythology held that their democracy had originally been instituted in the late 6th century thanks to an act of Tyrannicide – it was a myth, it wasn’t true historically, but it was none the less potent for that: in 336, most Athenians automatically identified democracy as non- or rather anti-Tyranny.

So, that tells us what the Law of Eucrates was – it doesn’t tell us how the Law came to be passed, and it doesn’t tell us why the Law was inscribed on a handsome stele of Pentelic Marble with a relief decoration above the text, and set up on public display in the Agora (civic centre) of Athens – where it was unearthed by the American School in the 1930s. Let’s begin with the relief decoration. That was put there partly because not all Athenian adult male voting citizens aged 18 or over (of whom there were about 25,000 in 336) were fully literate. And the image chosen – an image of the Goddess Demokratia crowning an image of Mr Joe Athenian citizen, as if he were a heroic victor at the Olympic Games – was to remind and reassure the Athenians that at least one very important Goddess was on their side. Besides of course Athene Polias (‘of the City’) and all the other Athenas – Promachos, Parthenos etc etc – not to mention Zeus and all the other gods of the official Athenian pantheon, and all the heroes and heroines both local and non-local (some of them depicted on the Parthenon) whom they worshipped. In Classical, democratic Athens religion and politics were inseparable.

OK, so now I want to go right back to the beginning, to the origins, of the Law of Eucrates. He was its proposer and original drafter, but between the moment of proposal and the moment of inscription and public display lay several crucial other moments. First, Eucrates had had to put a proposal in some verbal form to the Council (Boule) of 500, a standing committee of the Assembly (Ekklesia) responsible for managing its business, both preparing it and seeing that its decisions were carried out. The 500 were selected annually, by lot (the democratic mode), to serve for just one year in the first instance – they could serve again, but just once, and not in 2 successive years. It’s possible, even likely, that in 337/6 Eucrates was himself a Councillor – but he didn’t have to be, because ‘any Athenian who wished’ (the democratic principle) could put a proposal before one of the 40 – yes, 40 – pre-Assembly Council meetings, and the Council and its ‘presidents’ could decide either to welcome or to reject or to welcome and then debate/modify its terms. If a majority was agreeable that the Assembly should have a vote on it, then the Council could either send it forward just as the proposer (Eucrates) had formulated it or amend it and then put it forward to the Assembly in amended form – where it could be amended again. By this time it had turned into a probouleuma, something ‘pre-deliberated’.

The time for the next Assembly has arrived – imagine, in the tense situation of early 336, at least 6000 Athenian citizens in good standing (formal checks were minimal, but this was a relatively small, close-knit society) processing up onto the Pnyx and taking their seats on the ground. To hear the herald read out the proposal of Eucrates, now a probouleuma, whether amended or not in Council. The herald would then bellow out – this is in the open air – ‘who wishes to speak?’, implying that any one Athenian citizen who wished might stand up on the bema (speaker’s platform), a very egalitarian-democratic notion of public political freedom of speech (isêgoria). Probably, in actual practice, only known, experienced and authoritative speakers would for the most part have the courage and oratorical ability to do so, and probably there wasn’t much in the way of debate but just speeches PRO and CON – or PRO but suggesting amendments. A vote would then be taken, not a secret ballot but a raising of the right hands, and the numbers for or against would be ‘told’, that is assessed rather than individually counted – unless the voting appeared very close. As it would not have been in this particular case.

However, by 336 the Athenians had for long been cautious about passing any new laws – without the further scrutiny of another, much smaller committee, drawn - again by lot – from the permanent annual panel of 6000 Athenians who served during a year as jurors in the People’s courts. Once that committee had ratified the Assembly’s vote, Eucrates’s proposal was a law, and steps could be taken – by the relevant subcommittees of the Council – to have it inscribed, with accompanying relief decoration, and erected in the Agora.

Now… let’s transport ourselves back a century or more, to 448 BC/E. Then, there was no distinction drawn between a temporary or local decree and a general, permanent law, so there was no need for a further ratifying legislative step after the Assembly’s vote on the probouleuma proposing the (rebuilding of the) Parthenon. But – and it’s a big ‘but’ – implementing the Assembly’s vote on that was far far more complicated; and, secondly, though the Parthenon was visually and financially going to be the biggest thing on the new Acropolis, it was not actually the most important – in religious, cultural and political terms. That was the Temple of Athena of the City (Polias), which eventually was to come into being in the form of the Erechtheion on the opposite, north side of the Rock. And there were other temples and monuments besides the Older Athena Temple and the Older Parthenon that the Persians had destroyed in 480-479 and that the Athenians wanted to resurrect, and others again that the Athenians might want to add, e.g. an Athena of Victory (Nike) temple.

So, whoever was going to be the main or sole proposer of a rebuilt Parthenon was going to have to work out and put forward an immensely complicated proposal, a building programme indeed, and one that had to be costed, and then project-managed. I can’t go into all the finer details in the time available to me, but let’s just say that the ancients’ view – and pretty much the modern view too – is that the chief political architect of the Acropolis (re)building programme from 448 to the early 420s was the man depicted in that 1840s German painting I showed you earlier – Pericles son of Xanthippos of the deme Kholargos, to give him his full democratic name. Surely, though, he needed help – and the evidence suggests he could call on assistance from people who were not just the best experts in all the relevant fields but also personal friends of his. I’m thinking especially of Pheidias. Very very few other Athenian democratic politicians could do the same. And I do want to emphasise that Pericles was a (very) democratic politician. Despite his aristocratic and wealthy background, he devoted himself to what he took to be the best interests of the Athenian people, most of whom were not aristocratic or rich.

So, let us imagine that it was his proposal that in 448 went first to the Council then to the Assembly and received a majority vote in favour. What then? What we Brits call the nitty-gritty – deciding on a ballpark figure for costs (to be met by public not private funds), selecting architects, seeing that the architects got paid, and then that they, together with the contractors, employed all the necessary craftsmen and secured all the necessary materials. A bureaucratic nightmare - but somehow or other it was achieved, together with its cult-statue by Pheidias, and fast (by 432). The ultimate secret, I believe was the appointment of a subcommittee, reporting to the Assembly via the Council, of ‘Overseers’ (epistatai), just half-a-dozen, with a permanent secretary and deputy secretary. Some of their records or accounts – written, public, the democratic way – survive: I’ll cite just IG i3 449 dated 434/3 BC, conveniently available in ‘Attic Inscriptions Online’ with original Greek text and English translation and commentary. Pericles, typically, served his turn as an Overseer.

Nevertheless, Pericles – and the Athenians generally – received what we Brits call ‘stick’, severe criticism – not mainly because the Parthenon was a democratic building (though there were oligarchic critics, Athenians and others, who did badmouth both the Parthenon and Pericles for precisely that reason) but because it seemed out-of-scale, hubristic even, and too self-glorifyingly Athenian. After all, the Athenians – with the Spartans – hadn’t defeated the Persians singlehanded in 480 and 479. And as the Parthenon didn’t function only as a religious building – it became the City’s Treasury, its Fort Knox or Bank of Greece – there were those Greeks who saw it as not so much a symbol of democratic freedom but rather as a symbol of potential political and economic oppression. These were the Greeks who feared and resented what they thought of as an Athenian ‘empire’. Which it was – though it was also, paradoxically, a democratic empire! They did things differently then and there!

And it’s on that paradoxical note that I want to leave you. Yes, the Parthenon was – and is – supremely democratic, but not everyone saw it that way then - or see it that way today.