Culture and conflict often coexist in an uneasy and paradoxical manner; culture being an essential part of conflict and conflict resolution. Culture makes people understand each other better. Conflict resolution acts as a healing balm providing interaction between the concerned parties and the hope to overcome barriers.

Taking away and damaging the cultural heritage of a society is tampering with its identity. The history of art looting is lengthy and continuous. It begins possibly with Jason and the Argonauts looting the Golden Fleece. It continues with the habit of the Romans of looting art from conquered cities in order to parade it through the streets of Rome, before putting it on display in the forum. In Byzantium, the Hippodrome was adorned with looted art, and during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 the Crusaders looted the city itself. Cultural spoils were taken back to Venice to adorn the cathedral of St Mark, among them, the four gilded horses of the Apocalypse that remain in the city to this day.

In the ancient world, cultural pillage was an act of state planned to demonstrate the supremacy of the conqueror and underline the humiliation of the defeated. By the nineteenth century, however, such actions had been joined by the claim of the acquiring country to be the true heir of Classical civilization. Thus, Napoleon’s victorious armies began concluding a series of treaties with conquered states across Europe that allowed them to usurp artworks to stock the Louvre Museum.

From the colonial era to the Second World War, wars have provided opportunities for art looting on a massive scale, and the restitution of stolen cultural artefacts remains a dispute around the world. The trafficking of stolen art has become as widespread as drugs and firearms.

Private looting has always occurred alongside with state sponsored plundering, although it has evoked more disapprobation. The vandalism of the Parthenon sculptures by Thomas Bruce, seventh earl of Elgin, British Ambassador to the Ottoman court is the most notorious one and remains the archetypal case of looted artworks repatriation demand for more than 200 years.

Since the second half of the 20th century, states have adopted legislative instruments to regulate the illicit trafficking and the return of improperly removed cultural objects as part of a wider effort to enhance the protection of cultural heritage.

Restitution of cultural objects unethically removed from their countries of origin is a today’s global question. Cases concerning the circulation of cultural property are increasingly settled through diplomatic relationships. Museums are institutions representing reconciliation and as such, they have the duty to act ethically.

Antiquities of particular importance to humanity that were removed from the territory of a State in a questionable manner in terms of legality, as well as in an onerous way, need to be returned on the basis of fundamental principles enclosed in international conventions irrespective of time limits or other restrictions. They also need to be returned on the basis of legal principles, customary rules, and ethics. This need is also dictated by increased ecumenical interest for the integrity of the monument to be restored in its historic, cultural, and natural environment. Nobody may fully appreciate these antiquities outside their context. A characteristic example in this respect is the Parthenon Sculptures.

Lord Elgin was a fatal figure in the history of the looting of Greek antiquities. In 1799, he was appointed British Ambassador to the Sublime Porte at Constantinople. A year earlier, Napoleon had invaded Ottoman Egypt, and Britain hoped to become the sultan’s main ally in reversing the French conquest. The dispatch from London of a well-connected diplomat descended from the kings of Scotland who had previously served as a British envoy in Brussels and Berlin was itself a gesture of friendship toward the Turks.

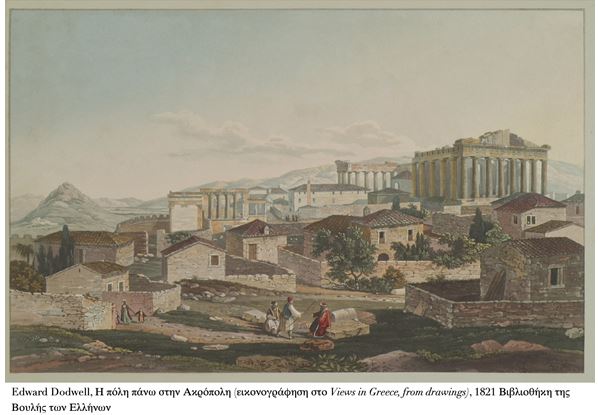

As well as competing in geopolitics, the British were rivalling French for access to whatever remained of the great civilizations of antiquity. Elgin seizes the opportunity for personal gain to acquire a huge collection of antiquities. His attention was focused primarily on the monuments on the Acropolis (the Parthenon topmost) which were very difficult of access and from which no one ever had been granted permission to remove sculptures.

His marriage to a wealthy heiress, Mary Nisbet, had given him the financial means to sponsor ambitious cultural projects. While traveling through Europe en route to Constantinople, he recruited a team of mostly Italian artists led by the Neapolitan painter Giovanni-Battista Lusieri.

Their initial task was to draw, document and mould antiquities in the Ottoman-controlled territory of Greece. The initially cloudy mission of Elgin’s artistic team culminated in a massive campaign to dismantle artworks from the temples on the Acropolis and transport them to Britain. By using methods of bribery and fraud, Elgin persuaded the Turkish dignitaries in Athens to turn a blind eye while his team removed those parts of the Parthenon, they particularly liked.

Elgin never acquired the permission to remove the sculptural and architectural decoration of the monument by the authority of the Sultan himself, who alone could have issued such a permit. He simply made use of a friendly letter from the Kaimakam, a Turkish officer, who at the time was replacing the Grand Vizier in Constantinople. This letter, handed out unofficially as a favour, could only urge the Turkish authorities in Athens to allow Elgin's men to make drawings, take casts and conduct excavations around the foundations of the Parthenon, with the condition that no harm be caused to the monuments.

On 31 July 1801, the first of the high-standing sculptures was hauled down. Between 1801 and 1804, Elgin's team was active on the Acropolis, stripping, hacking off causing considerable damage to the sculptures and the monument. Eventually Elgin’s team detached half of the remaining sculpted decoration of the Parthenon, together with certain architectural members such as a capital, a column drum and one of the six caryatids that adorned the Erechtheion temple, as they could not found an available ship to take all six away! “I have been obliged to be a little barbarous,” Lusieri once wrote to Elgin.

London and Athens now hold dismembered pieces of many of the sculptures. Large sections of the Parthenon frieze, an extraordinary series of relief sculptures depicting the procession of Greater Panathenaia, the most important festival held in honour of the city’s divine patroness Athena, numbered among the loot.

Of the 97 surviving blocks of the Parthenon frieze, 56 have been removed to Britain and 40 are in Athens. Of the 64 surviving metopes, 48 are in Athens and 15 have been taken to London. Of the 28 preserved figures of the pediments, 19 have been removed to London and 9 are in Athens.

The shipping of these precious antiquities to Britain was fraught with difficulties. One ship sank and the sculptures, after prolonged exposure to the damp in various harbours, eventually arrived in England three years later. In London, they were shifted from sheds to warehouses, because Elgin had been reduced to such penury by the enormous costs of wages, transportation, gifts and bribes to the Turks, that he was unable to accommodate them in his own house. So, after the mortgaging of the collection by the British state, he was obliged to sell the Parthenon Sculptures to the government, for £35,000—less than half of what Elgin claimed to have spent. Finally, the British Government transferred the Sculptures to the British Museum in 1817. In 1962, they were placed at the Duveen Gallery. Even after they arrived at the British Museum, the sculptures received imperfect care. In 1938, for example, they were “cleaned” with an acid solution.

Prior to the transaction a Committee was appointed to consider the purchase and the evidence, it gathered was placed before Parliament. A debate took place, where many voices expressed their scepticism and disapproval. Even thoughts about the return of the Marbles were expressed for the very first time. Hugh Hammersley, a Member of Parliament, first raised the question in the House of Commons. Strenuous objections were heard outside Parliament as well, the most impassioned being that of Lord Byron, a poet and fellow member of the Anglo-Scottish aristocracy. Elgin was denounced as a vandal in sonorous verses by Lord Byron.

Contrary to Elgin’s stated fears, the sculptures that remained in Athens did not vanish. After 1833, when the Ottomans left the Acropolis and handed it to the new nation of Greece, the great citadel and its monuments became a focus of national pride. Protecting, restoring and showcasing the legacy of the Athenian golden age has been the highest priority for Greeks since then.

The removal of the so-called Elgin Marbles has long been described as an egregious act of imperial plunder.

Not surprisingly, the British Museum has so far refused all requests to give up one of its most popular exhibits. The Parthenon sculptures have become the most visible, and notorious, collection of Acropolis artifacts still housed in museums across Europe, often with the justification that such objects are emblematic of European civilization, not just of Greek heritage.

The British Museum relies on the supposed legality of an Act of Parliament. The Trustees shelter behind the argument that it is the law – that they are entrusted with these artefacts and cannot divest themselves of them. In reality, as the late Eddie O’Hara, former MP and Chairman of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles (BCRPM) stated, “the government simply needs to legislate to say ‘yes, this is possible.’ – as they did with Nazi loot.”

Even this most difficult of disputes can be resolved with the support of both Museum of Trustees and the UK Government by amending the 1963 Act or by enacting separate legislation. An Act of Parliament could be an Act of Conscience! As Janet Suzman, Chair for the BCRPM declared, the Trustees of the British Museum must get their heads together and break the shackles preventing the just return of Greece’s precious heritage to Athens.

Today, the defenders of keeping the Parthenon Sculptures in the U.K. are looking increasingly lonely. A particularly important development in the long-running request marks both the transformation of British public opinion and the changing trend of museums for the repatriation of cultural treasures, together with the eloquent request for reunification by Greek Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, submitted to his counterpart, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, during his visit in London last November.

Even, The Times, the flagship newspaper of the British establishment, made a historic turn to support the reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures: "Τhey belong to Athens, they must be returned”. The main article of The Times, in an unprecedented fashion, stating that it is like taking Hamlet out of the First Sheet of Shakespeare’s works and saying that both can still exist separately, recognizes the uniqueness of the Parthenon Sculptures!

This support for Greece's request is welcomed by all those that have reinforced the diplomatic route for the reunification of the sculptures, applying constant and methodical pressure and garnering assistance from the international community. It was preceded by the unanimous decision of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Commission for the Return of Cultural Property to Countries of Origin (ICPRCP), which at its 22nd Session on 29th September 2021, adopted for the first time, in addition to the usual recommendation, a text focusing exclusively on the return of Parthenon sculptures. This new text, acknowledging the intergovernmental nature of the subject, was in direct contrast to the British side, which has consistently argued that the case concerns the British Museum. The Commission calls on the United Kingdom to reconsider its position and hold talks with Greece.*

*quotation of the text presented by the Greek delegation to UNESCO's ICPRCP.

Last week, the Μuseum’s chairman George Osborne said: "I think there is a deal to be done – whereby the marbles could be shown in both Athens and London, and as long as there weren’t “a load of preconditions” or a “load of red lines”. Since then, a number of British Lawmakers have also voiced their support for the return of the marbles, and a group of scholars and advocates of the sculptures ‘demonstrated', at the British Museum on the occasion of the 13th birthday of the Acropolis Museum.

The Acropolis Museum’s director general, Professor Nikos Stampolidis, responded with a statement, in which he described the Parthenon Sculptures as representing a procession that symbolized Athenian democracy. “The violent removal of half of the frieze from the Parthenon can be conceived, in reality, as setting apart, dividing and uprooting half of the participants in an actual procession, and holding them captive in a foreign land,” Prof. Stampolidis said. “It consists of the depredation, the interruption, the division and dereliction of the idea of democracy. The question arises: Who owns the ‘captives?’ “The museum where they are imprisoned, or the place where they were born?”

A precursor to the return is the agreement between Italy and Greece. The “Fagan fragment” of the Goddess Artemis, became the first permanently repatriated marble fragment of the sculptures to be restored on the Parthenon frieze, from the Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeology Museum in Palermo, on June 4. It was taken at the same time as the forceful removal of the Parthenon Sculptures by Lord Elgin, and later sold to the University of Palermo.

Meanwhile European governments are rushing to announce policies to return cultural goods to their countries of origin. France returned 26 items, 16th and 17th century bronze art pieces, of unparalleled art to Benin last October, and Germany announced that it would return to Nigeria, the spoils of Benin. In April, Glasgow city council voted to return 17 Benin bronze artefacts looted in West Africa in the 19th century. The Belgian government as well, has agreed to transfer ownership of stolen items from its museums to African countries of origin. Lately, the Plenary Session of the 76th UN General Assembly adopted the decision promoted by Greece for the return of cultural goods to their countries of origin.

Since regaining independence in 1832, successive Greek governments have petitioned for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures. Melina Mercouri, Greek minister of Culture, reenergized the repatriation campaign, by making a request in 1982 for the Greek government to return the Parthenon Sculptures to the UNESCO General Conference on Cultural Policy in Mexico.

The new Acropolis Museum of Athens, which opened in 2009, was built within sight of the actual Parthenon with the goal of eventually housing all the surviving elements of the Parthenon frieze. The Museum’s magnificent glass gallery, bathed in Greek sunlight and offering a clear view of the Parthenon, is the perfect place to reintegrate the frieze and allow visitors to ponder its meaning.

Greece's constant demand for the reunification of the stolen Parthenon Sculptures with the mutilated ecumenical monument is a unique case based on respect for cultural identity and the principle of preserving the integrity of world heritage sites.

As Professor Paul Cartledge, Vice President of BCRPM rightfully said: ‘The key word is ‘Acropolis’. The Parthenon, a UNESCO World Heritage site, derives its significance ultimately from its physical context. A good deal of the original building has miraculously been preserved and in recent times expertly curated. The gap between the Acropolis Museum’s Parthenon display and that in the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum is simply immeasurable. Over and against the alleged claim of legality, there is on our side the overriding claim of ethical probity. Times change, and mores with them.”

The United Kingdom can only benefit from the long-awaited gesture, not of generosity, but of justice. The reunification will finally be given its time.

*The article above formed part of a presentation that Sophia Hiniadou Cambanis gave at the Thessaloniki International Conference : “Art communicating conflict resolution: An intercultural dialogue” co-organized by the Municipality of Thessaloniki and the UNESCO Chair “Intercultural Policy for an Active Citizenship and Solidarity” of the University of Macedonia, on June 30th 2022.

**Sophia Hiniadou Cambanis is Attorney at Law and Cultural Policy & Management Advisor at the Hellenic Parliament