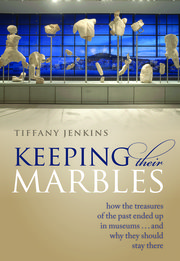

The photograph on the dust jacket of Tiffany Jenkins’s Keeping Their Marbles shows a museum display of breath-taking elegance and beauty. Two dozen small fragments of marble sculptures seem to float in mid-air, fixed to one another and to the plain white base of the display with simple brushed steel rods. A good threequarters of the original sculptural group is lost, but the viewer’s imagination fills in the gaps with little effort. At the left, a female figure dashes in, reaching towards a rearing horse, perhaps pulling at its flying reins; at the centre, two huge figures, one male, one female, stand locked in struggle. In the sculptures, everything is motion and energy. By contrast, the gallery space that surrounds them is crisp and minimalist, with nothing to distract the viewer’s attention from the astonishing objects on show – except perhaps the wooded hills just visible outside the window, with the sun setting behind them. It is hard to imagine a better illustration of the book’s subtitle: “How the treasures of the past ended up in museums . . . and why they should stay there”.

The photo shows the surviving sculptures from the west pediment of the Parthenon, displayed with sensitivity and tact in a museum space of the most extraordinary beauty. The museum in the photograph is the Acropolis Museum in the city of Athens, one of the world’s truly great museums, which houses not a single item looted, stolen, or bought from a country poorer than the Athenians’ own. The female figure on the left, a study in kinetic energy, is the goddess Iris. The head of the goddess is original, but her body is a plaster cast; Iris’s body today stands in the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum. Dull is the eye, wrote Byron, that will not weep. He was right.

Read the full article by Peter Thonemann on Tiffany Jenkins' book here

The article was printed on 29 April 2016

Dr Peter Thonemann

Dr Peter Thonemann

The following week (06 May) the Editor printed a letter submitted by a reader, James Hall from Winchester:

1GL-Letters to the Editor-0fff06.pdf

There was, as you might have anticipated, a long set of email exchanges amongst BCRPM members.

Hon President Prof Anthony Snodgrass wrote a reply to the letter by James Hall.

Sir, - The odd cultural judgment apart - Byron as an ‘opportunistic buffoon’ - the great length of James Hall’s letter on the Parthenon Marbles (May 6) is down to the number of factual misstatements, some new, some worn by repetition, that he insists on including. There is no space to do more than list them, before picking out what is perhaps the prize specimen.

‘Most large sculptures in Greek museums have been stripped from temples (unearthed, not ‘stripped’ - that was left to Elgin); ‘imported slaves built the Parthenon’ (a tendentious exaggeration); ‘the National Museum contains work from colonies throughout the Aegean’ (a devious word-play on the associations of the word ‘colony’); the Acropolis Museum is ‘poorly attended’ (yet it somehow attracts greater numbers than that minority of British Museum visitors who actually enter the Duveen Gallery); ‘Those professionally involved with Greece presumably fear for career and well-being if they come out in favour of retention’ (he must be alone in so presuming).

As a member of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, I am flattered that he credits our movement with ‘great social, political and academic clout’, but that is surely another exaggeration; and it is equally far-fetched to call our opponents ‘a silent majority’ when they are neither silent nor a majority - as a glance, respectively, at the reactionary press or at a series of periodic U.K. opinion polls will show.

But: ‘the Marbles have been well loved, treated and contextualized’ in Bloomsbury’ - that is going too far. Well contextualized in the acknowledged ‘joylessness’ of the Duveen Gallery, with the frieze turned inside out and the arrangement doctored to hide the gaps ? And was James Hall around in 1999 when the British Museum hosted a colloquium on the ‘cleaning’ operation, carried out sixty years earlier at Duveen’s insistence, where one of its own Keepers described the cleaning as ‘a scandal, and the cover-up … another scandal’ ? Many of the London sculptures lost up to a millimetre of their surface in that operation; to see the original surface detail of the frieze slabs, one must revert to the pieces in Athens that had been ‘at the mercy of the toxic elements’ - well yes, but these have still turned out to be more merciful than the chisels and abrasives of Duveen.

Comments powered by CComment