The two-hundred-year-old debate over the ownership and placement of the Parthenon Sculptures, otherwise known as the Elgin Marbles, is one that has renewed relevance in today’s world. Repatriation controversies have become a crucial facet of international museum law and relations, while the concurrent completion of the New Acropolis Museum in Athens and the Greek economic crisis inject new factors into the specific case of the Parthenon Sculptures. The new museum allows for the conversation to be redirected towards achieving repatriation on the grounds of artistic and archaeological integrity and unity, rather than debates over purchase authentication and trustee ownership. My thesis reviewed the existing arguments for repatriation[i], but supplemented them by developing the underutilized argument of aesthetic integrity. I promote the concept of the Parthenon’s formal qualities and the need for cohesion among those qualities as the basis upon which the debate over placement and display of the sculptures should be governed.

Given the dearth of literature since the completion of the new Acropolis Museum (AM), I compare the authenticity and educational experience of the displays in the new AM and the British Museum (BM). Put simply, the estranged marbles cannot be considered or understood as autonomous artworks, as doing so ignores and diminishes the formal qualities of the Parthenon and the intent of its creators. My research examines precisely how the BM’s division of the sculptures continues to injure the integrity of the Parthenon, as well as how the museum’s presentation of the sculptures does a disservice to the archaeological record.

An examination of the Parthenon exhibit in the BM demonstrates a display that is contradictory to both the original structural and instructive aspects of the Parthenon. The displays in the BM are unnatural and serve to disrespect the Parthenon and its sculptures, inhibiting their unity both literally and conceptually. The layout also severely impairs both the viewer’s comprehension and the sculptures’ physical and iconological integrity. For example, in the BM, sections of the South frieze are estranged from the South metopes intended to accompany them. The South metopes are actually displayed along with the East and West pedimental programs (whose metopes are in Athens). The South and North frieze sections in the BM actually face each other, which greatly hinders the proper viewing progression of the narrative for all viewers unaware of the precise order of the Ionic (continuous) frieze.

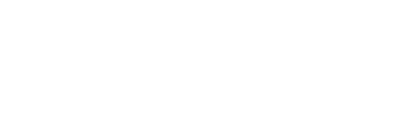

One particularly interesting illustration of the connections that exist between the different types of sculpture on the Parthenon can be seen in an example that Olga Palagia points out, on the Northeast corner of the building. The metope on this corner (East side, metope 14) depicts Helios, the sun god who brings in the day, and his chariot with several horses. In the Parthenon’s original state, directly above this block, the horses of Selene, the moon goddess and sister to Helios, appear in the pediment facing the opposite direction.[ii] This juxtaposition of these opposing forces, who are related both by mythology and proximity, can hardly be random and is a poignant example of the methodical calculation and planning that went into the creation of the Parthenon. In comparison, in the British Museum, Selene’s horse faces a metope plucked from the South side of the building.

Figure 1 and 2: Selene's horse and the display map in the British Museum. Although not labeled, the metopes that the horse faces are from the South metope-triglyph frieze. Source: Parthenon Gallery, British Museum, London. Photograph taken by author, 2014.

During my time in the BM, I watched as viewers hopped from South frieze to West pediment, to North frieze, to South metopes, all the while believing that they had gleaned the true meaning and message of these spectacular sculptures. This is an easy trap to fall into—the BM’s entire exhibition program of the Parthenon Sculptures works to maintain the focus on the magnificence of the individual sculptures, and simultaneously aims to deemphasize their connection to the Parthenon. Indeed, throughout the BM exhibition, there are only two small photographs (roughly 5 in. x 7 in.) of the Parthenon. In addition, nowhere in the entire exhibition can the viewer see a reconstruction, either physical or virtual, of all the remaining sculptures reunified.

By intentionally emphasizing the sculptures and deemphasizing their connection to the monument, the BM exhibition protects the viewer from the more complicated ethical issues. The sculptures are so beautiful that this is rather easy to achieve. Viewers are so entranced by the magnificence of the sculptures that it becomes extremely difficult to contemplate the notion that something is wrong with

the picture, so to speak. The concerning presentation of the marbles is a symptom of the bigger problem, namely the idea that the sculptures are independent, autonomous works that are conceptually free-standing, as well as physically free-standing. This line of thought should not be allowed to be perpetuated—it delegitimizes the conceptual basis of the Parthenon, just as it literally detracts from its physical integrity.

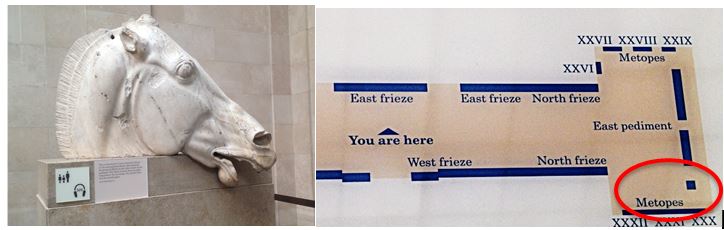

As I continued to document the sculptures’ layout, two visitors made a remark that quickly cuts to the heart of this issue. We were standing in front of some of the South metopes, many of which are missing heads, feet, and torsos from the figures they depict. Numerous wall texts read “The head is in Athens,” or “The feet are in BM Gallery 18b” (there are 3 separate Parthenon galleries in the BM). The man standing next to me sarcastically asked, “So what, is there an exhibition of heads somewhere?” This little comment speaks volumes—it communicates the confusion and frustration viewers feel at the disunity of the Parthenon’s elements and the disorganization of their display in the BM.

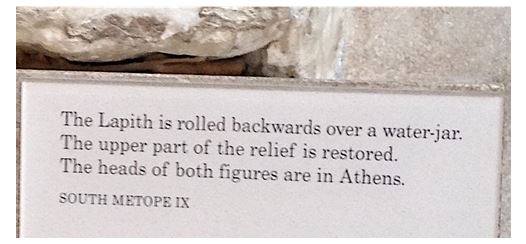

This sense of disunity is only enhanced when one continues to read the wall texts, particularly the didactics for the metopes and pedimental figures. Numerous pieces are missing heads, torsos, or feet, not because the pieces are destroyed, but because they are housed elsewhere, mainly in Athens. For example, in the West pediment room, there are seven pedimental figures and eight South metopes. Of the fifteen sculptural pieces in this room, the wall labels state that ten are missing body parts (see fig. 3). The pieces are in either the Acropolis Museum in Athens, the Wurzburg or Copenhagen museums, or, as is the case with the foot from a suspected torso of Hermes, in gallery 18a. Gallery 18a, which is separate from gallery 18, has an entire case of sculptural fragments (see fig. 4), which serves to aptly highlight the disunity and fragmentation of the overall presentation of the sculptures in the BM.

Figure 3: Wall text demonstrating the problem with the division of the sculptures. There are many other wall texts similar to this one in the Duveen Gallery. Source: South Metope Wall text, Duveen Gallery, British Museum, London. Photograph by author.

Figure4: Display case of sculptural fragments from the West Pediment of the Parthenon. Source: Gallery 18a, British Museum, London. Photograph by author.

To remove figures from the composition, or sections from the frieze, is to inhibit the whole building’s success and detract from current understandings due to a lack of proper context for the removed pieces. The sculptures in the BM are fragments, which, as Jennifer Neils states, are “simply trophies that make little sense aesthetically or intellectually in isolation.”[iii] It is not for modernity to arbitrarily decide which elements can be “stand-alone” pieces after they have been destructively distanced from their context. By prioritizing the missions of even the most revered universal museums over that of context and archaeological and aesthetic integrity, one negates the significance, meaning, and value of artifacts and museum collections.

The irrefutable logic of unity and cohesion can no longer be ignored, as the AM offers a spectacular—and highly superior—display that acknowledges and exalts the formal qualities of the Parthenon. In contrast, the BM presents the sculptures as conceptually freestanding pieces—a choice which neglects their context and higher purpose in the sculptural program of the Parthenon. The BM’s Parthenon Galleries fail to encourage an accurate understanding of the unity of the Parthenon and the relationships among its parts, and fail to appropriately present, and therefore connect, the sculptures to the monument. Despite Neil MacGregor’s constant use of the phrase “different and complementary stories,”[iv] let us be clear: There is no alternative interpretation of the Parthenon in the sense that it was created as a single, unified, site-specific monument. The BM has shown its disingenuous stripes through its botched attempts at rationalizing the retention of the marbles in London. MacGregor would have visitors feel as though they are, in fact, seeing a “complementary” perspective; in reality, visitors are seeing nothing more than a thinly veiled ploy to downplay the sculptures’ proper context—a maneuver that serves no purpose other than to attempt to ethicize a continued wrong.

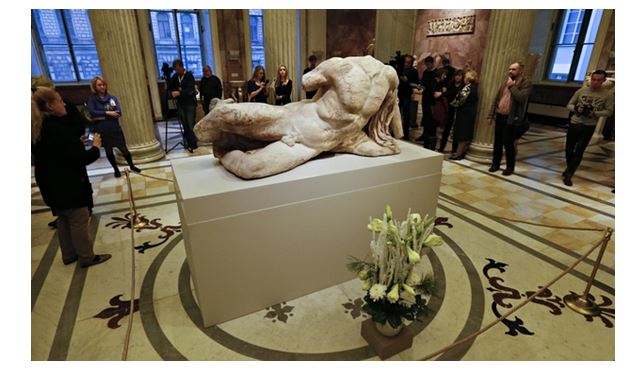

Figure 5: Ilissos sitting in isolation in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. Source: Helena Smith, The Guardian, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/05/parthenon-marbles-greece-furious-british-museum-loan-russia-elgin.

Loan to the Hermitage

The BM’s disturbing efforts to force the complete disassociation of the marbles from the monument reaches new levels of audacity with the recent back-alley loan of Ilissos, the personification of the river of the same name, to the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Aside from the egregious diplomatic implications of loaning a highly contested piece of art to a country which is currently annexing the Crimea, committing numerous violations of international law, and facing severe sanctions by world powers such as the European Union, the loan serves to epitomize the BM’s campaign to propagate the myth that the sculptures are iconologically independent works. While MacGregor congratulates himself and attempts to pass off the loan as a convivial Hermitage birthday celebration, Ilissos, now twice divorced from his context, is left to sit in isolation. The loan of Ilissos definitively proves the museum’s utter disrespect for the monument; one cannot venerate the Parthenon while distributing its already-fragmented elements across the globe, bereft of any context. Such an act is a direct violation of the formal qualities of the Parthenon.

Concluding Thoughts

The debate is lengthy and convoluted; however, offering a methodology based on respecting the formal characteristics of the Parthenon is the first step to guiding the dispute towards progressive solutions. Placing the emphasis back on the significance and formal traits of the Parthenon is the proper method by which the debate must be continued. This approach upholds the grandeur of the Parthenon and affirms the realities of its design and purpose. In contrast, arguments that fail to take into account the formal artistic and archaeological qualities of the Parthenon deny its importance and refute its validation. Claims based on dubious acquisition documents, false assertions of ownership, and colonialist entitlement attitudes are mere distractions and have no place in progressing the debate and achieving a resolution. Aesthetic and archaeological integrity irrefutably negate any and all arguments against reunification, and if museum specialists, art historians and archaeologists, policy makers, and legislators work collaboratively through this paradigm, there is surely hope for repatriation of the sculptures.

Selected Bibliography:

Neils, Jennifer. The Parthenon Frieze. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Palagia, Olga. “Fire from Heaven: Pediments and Akroteria of the Parthenon.” The Parthenon: From Antiquity to Present, ed. Jenifer Neils. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Smith, Helena. “Parthenon Marbles: Greece furious over British loan to Russia.” The Guardian. December 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/05/parthenon-marbles-greece-furious-british-museum-loan-russia-elgin. Accessed December 20, 2014.

“The Parthenon Sculptures,” The British Museum, 2008, http://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/statements/parthenon_sculptures.aspx.

Endnotes

[i] I use the terms repatriation and reunification interchangeably. These terms are not intended to mean the physical rejoining of the sculptures to the Parthenon, but rather the return of the sculptures to Athens, Greece, for their inclusion in the Parthenon Gallery of the new Acropolis Museum.

[iii] Jennifer Neils, The Parthenon Frieze, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 257.

Glenna Gray is a 2014 graduate of Randolph College in Lynchburg, VA. She is passionate about researching art repatriation issues and the legal complexities that surround them. In her pursuit to gain knowledge in the field of cultural heritage preservation, she has worked with researcher Tess Davis from the University of Glasgow, assisting with research regarding the antiquities looting in Cambodia during the French explorations. Glenna recently completed an Honours Thesis on the issue of the Parthenon Sculptures, and travelled to London and Athens to assess the museum displays, presentation authenticity, and educational outcomes of the British Museum and Acropolis Museum’s Parthenon galleries. In fall 2015, she will begin a Master’s program at Rutgers University, for a further degree in Cultural Heritage and Preservation Studies. Her current research interest pertains to the diplomatic tensions between Cyprus and the Turkish occupying forces, and the implications for the state’s rich material culture.

Comments powered by CComment