Dear Sir,

Jonathan Jones (29 January) writes that those who argue for the return of the Parthenon sculptures to Greece are driven by a belief that ‘every work of art should stay in its original location, as it only has meaning in its original context’. Mr Jones sees this belief, correctly, as dangerously illiberal and nationalist: ‘If you follow this through to its logical conclusion, there should be no international sharing of images and ideas. Every altar piece in the National Gallery would have to go back to the church it was made for’.

The altarpiece analogy is a good one. In the late eighteenth century, Veronese’s spectacular Petrobelli altarpiece from the small town of Lendinara near Venice was crudely hacked to pieces. The four surviving fragments, each of them meaningless in isolation, are today housed in four different museums. The issue is not whether these four fragments of a single painting should be ‘sent back’ to Lendinara; it is whether Veronese’s magnificent painting should be ‘reunified’, as it was so dramatically and movingly in Dulwich Picture Gallery back in 2009.

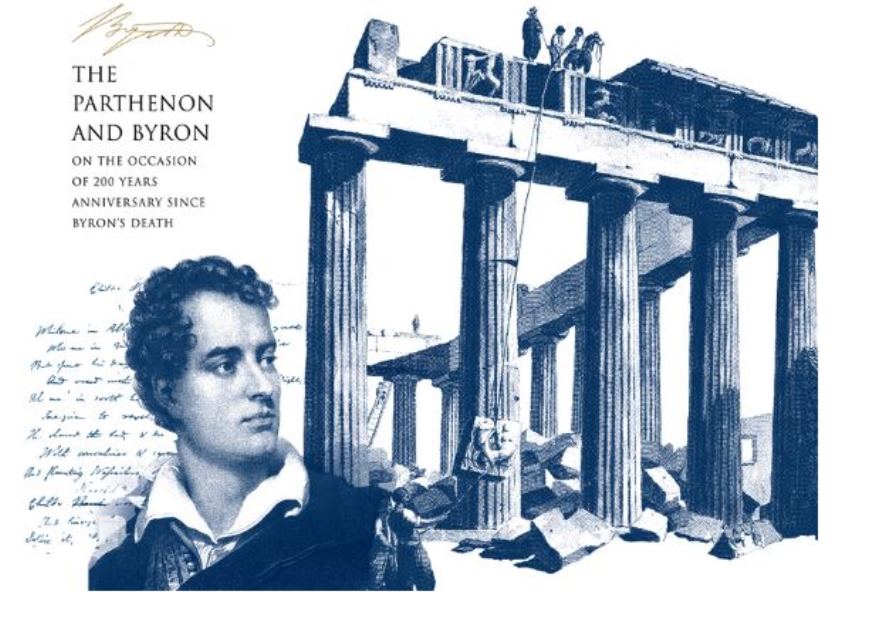

Most of those who are committed, as I am, to the reunification of the Parthenon marbles are not motivated by a crude nationalist urge to ‘send them home’ – Greek art for the Greeks. I am moved by the absurd spectacle of one of the world’s great aesthetic and cultural treasures crudely hacked in two, with both halves horribly diminished as a result: 80m of a single glorious religious procession in London, the remaining 50m in Athens; the body of the goddess Iris in the Duveen Gallery, her head in the Acropolis Museum. Reunification, not restitution.

Peter Thonemann, Wadham College, Oxford and a Member of BCRPM

Alexi Kaye Campbell also wrote to the Guardian

As a member of the British Committee for the Repatriation of the Parthenon Marbles who recently argued (and happily won) against Jonathan Jones at the UCL debate which he mentions in his recent article, I presumptuously assume I am included in his description of 'the passionate proponents of Greece’s claim’ . He goes on to say that people such as myself 'need to explain how their arguments differ from any other variety of national populism’ . Funny, I thought I had done just that at UCL, but I shall do so again in case he missed my point.

On that evening, I had made the distinction between patriotism and nationalism and had alluded to how I believe nationalism is what happens when patriotism is thwarted. I had said that as a relatively new modern state, albeit with an extraordinary ancient heritage, Greece’s need to forge its contemporary identity after hundreds of years of occupation, cultural evisceration and adversity, often has to look to its glorious ancient history and achievements for confidence and pride. So there is some symbolism in its wish to see the marbles reunited with the monument from which they had been taken when Greece was under Ottoman occupation, there is little doubt of that. That aspiration, to see such a potent symbol of Greek selfhood made whole again, seems to be an understandable expression of patriotism, especially from a small country which has suffered a tumultuous and often traumatic history. To describe Greece wanting back a piece of art which is an integral part of its most iconic monument as an ' act of national populism’ is a slightly hysterical allegation, and that it comes from someone who labels any argument for the return of the marbles to Greece as purely emotional and unthinking, is rich. National populism is an ugly and aggressive movement; asking for something of huge significance which has been taken from you when you were under foreign occupation is more an act of simple justice. If neither Jonathan Jones, a Brit, or Hartwig Fischer, a German, can quite understand this notion or sympathise with it, may I suggest it may have something to do with with the fact that both of them come from nations and cultures that have for the most part been the colonisers, and not the colonised. In that vein, a somewhat anglocentric view of the world is betrayed when Jones laments that 'Keats was not rich enough to visit Greece' and see the marbles whilst not seeming all that concerned with the millions of people from Greece, or anywhere for that matter, who will never be able to afford to ‘expand their horizons’ by traveling to the world museum, which just happens to be in London.

Having said all that, the most nefarious aspect of Jonathan Jones’ piece is that it attempts in true paternalistic style, to create a climate in which those wishing for the return of the marbles are portrayed as being almost exclusively driven by emotion in contrast to the sensible and pragmatic Enlightenment views of those defending the British Museum position.

For many years, I sat on the fence when it came too this topic. As an Anglo-Greek, proud of both my heritages, I could see both sides of the argument. Before the creation of the stunning Acropolis Museum, I agreed with the BM’s position that Greece did not have somewhere adequate to house them. But then, I changed my mind.

Some of that change comes from the Greek patriotism I have described above, and which, like all patriotism, I will concede, does have an emotional dimension to it. But much more than that, after numerous visits to both the Parthenon and the Duveen Galleries I came to realise that not only for sentimental reasons, but for artistic, aesthetic, and intellectual ones, the marbles need to be seen with the extraordinary building from which they have been prized. This, in my mind, and despite my opinions on the history of colonialism and its legacies, is what separates this claim from the many others now being made for the repatriation of works of art in museums across the world. To put it quite simply, the Parthenon, which stands triumphant as a symbol for all humanity under the Attic sky, should be seen whole, entire, complete. An eternal symbol of democracy, more essential than ever before.

What would be a truly creative act, and a courageous one, would be for the British Museum to do the right thing.

Alexi Kaye Campbell, Member of the BCRPM

Comments powered by CComment