22 September 2018

When the Parthenon in Athens fell into ruins in early the 1800s, a British ambassador with permission from the Ottoman Empire preserved about half the sculptures, which are now at the British Museum. But Greeks for centuries have wanted them back; the deal was made before their country fought for independence from the monarchy. NewsHour Weekend Special Correspondent Christopher Livesay reports.

Watch the PBS Newshour podcast here or listen to the audio here.

Read the Full Transcript

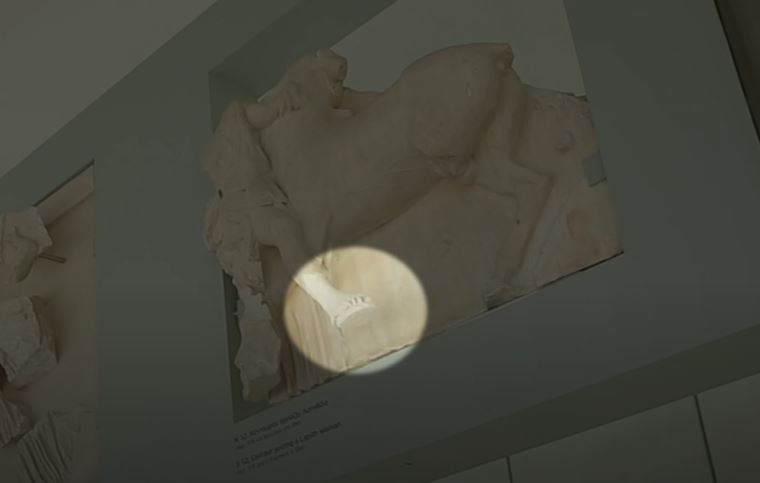

A highlight of London's British Museum is one of its earliest acquisitions, the Parthenon Marbles. These sculptures once decorated the great 5th century BCE temple on the Acropolis in Greece. Considered among the great achievements of the classical world, they depict mythical creatures, stories of the gods along with average people.

They are very significant and important masterpieces, really, of the ancient Greek world.

Hannah Boulton is the spokesperson for the British Museum. She admits that how these classical works came to be in England is a sensitive subject, one the museum takes some pains to explain.

I think it, obviously, has always been a topic of debate ever since the objects came to London and into the British Museum. It's not a new debate.

The story starts in the early 1800s. The Parthenon had fallen to ruin. Half the marbles were destroyed by neglect and war. Then, a British ambassador, Lord Elgin, made an agreement with Ottoman authorities who were in control of Athens at the time to remove some of statues and friezes. He took about half of the remaining sculptures.

And then he shipped that back to the UK. For a long time it remained part of his personal collection so he put it on display and then he made the decision to sell the collection to the nation. And the Parliament chose to acquire it and then pass it on the British Museum. So we would certainly say that Lord Elgin had performed a great service in terms of rescuing some of these examples.

But Greeks don't see it that way. For decades now, they have argued that the Ottomans were occupiers, so the deal with Elgin wasn't valid, and the marbles belong in Greece. Why does Greece want to have the Parthenon Marbles back in Athens?

It's not just bringing them back to Athens or to Greece. That's where they were created. But this is not our claim. Our claim is to put back a unique piece of art. To put it back together. Bring it back together.

Lydia Koniordou was Greece's Minister of Culture from 2016 to 2018. We met her at the Acropolis where the Parthenon temple stands overlooking Athens.

So first it was Lord Elgin who removed 50 percent.

Almost 50 percent.

All of the marbles, she says, have now been removed from the monument for protection from the elements. Then it was Greece that consciously decided to remove the remaining.

Yes, the scientists that were responsible decided to remove and take them to the Acropolis Museum. It was nine years ago when the Acropolis Museum was completed.

In fact, the Acropolis Museum was built in part as a response to the British Museum's claim that Greece did not have a proper place to display the sculptures. The glass and steel structure has a dramatic view of the Acropolis, so while you're observing the art you can see the actual Parthenon. The third floor is set up just like the Parthenon, with the same proportions. These friezes, from the west side of the temple, are nearly all original. On the other three sides, there are some originals but also a lot of gaps, as well as white plaster copies of the friezes and statues now in Britain.

We believe that one day we could replace the copies with the orginals to show all this unique art in its grandeur. Every block has two or three figures and here is only one.

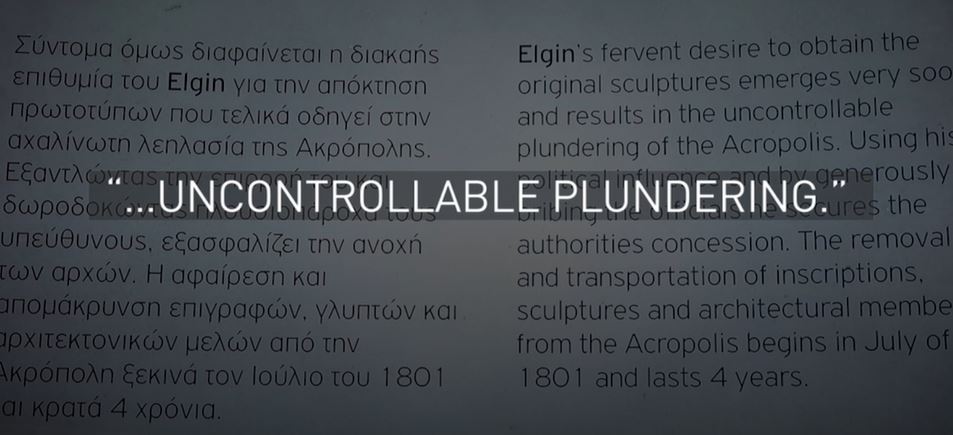

Dimitrios Pandermalis is the Director of the Acropolis Museum where the story of the missing marbles differs widely from that of the British Museum. Presentations for visitors portray Lord Elgin critically. One film shows the marbles flying off the Parthenon and calls it the uncontrollable plundering of the Acropolis. You have these videos that actually show how the pieces were removed. Another film depicts how one of the marbles was crudely split by Elgin's workmen.

He damaged the art pieces, yes.

He did damage some of these pieces.

Of course, it was to be expected.

The British Museum disputes the claim Elgin damaged the sculptures. It also sees it as a plus that half the collection is in Britain and half in Greece.

I think the situation we find ourselves in now we feel is quite beneficial. It ensures that examples of the wonderful sculptures from the Parthenon can be seen by a world audience here at the British Museum and in a world context in terms of being able to compare with Egypt and Rome and so on and so forth. But we feel the two narratives we are able to tell with the objects being in two different places is beneficial to everybody.

But Pandermalis says rather than being in two places the sculptures should be reunified, literally. He showed us examples around the museum, including one that is almost complete save for one thing.

So this sculpture is original except the right foot.

And this. The chest of the god Poseidon. So the marble portion in the center where we can see clearly defined the abdomen, that's original but the surrounding portion in plaster, the shoulders, that's in London. So the piece has been completely split in half.

Yes.

And perhaps most dramatic, this frieze. So the darker stone is the original and the white plaster that represents what's in the British Museum.

Yes. Exactly.

And here it is in the British Museum. The missing marble head and chest floating in a display space.

It just doesn't make sense. It's like cutting, for instance, the Last Supper of Da Vinci and taking one apostle to one museum and another apostle to another museum. We feel also it's a symbolic act today to bring back this emblem of our world. To put it back together.

If you bring back this emblem, aren't there untold other emblems that need to be brought back. Is this a slippery slope?

We do not claim, as Greek state, we do not claim other treasures. We feel that this is unique. This claim will never be abandoned by this country because we feel this is our duty.

As for visitors to the Acropolis museum. How do you feel about the fact that half the collection is in the British Museum?

Not good.

The Roscoe family is from Ohio. What do you guys think?

I think it would be nice to have them in one spot where they originated.

You're coming here to see the history of it so it would be nice to see the complete history rather than replicas.

You've seen them in the British Museum. So what do you think about the fact that the collection is kind of split.

It's sad. When you see this. I think this museum is a phenomenal place to display them. It's beautiful and they way it's been built almost waiting to have them back. It's interesting.

As recently as May the Greek President, Prokopios Pavlopoulos, told Prince Charles that he hoped the Marbles would be returned. And the British opposition Labor leader Jeremy Corbyn has said he too is in favor of returning the Marbles to Greece. But the British Museum's position is the marbles in its collection are legally theirs. They would, however, consider a loan. After all, the British Museum regularly loans pieces from its collection to other museums around the world.

I think we would certainly see there being a great benefit in extending that lending and trying to find ways to collaborate with colleagues, not just in Greece but elsewhere in the world to share the Parthenon sculptures that we have in our collection.

But sharing the sculptures is not what the ancient Greeks who created them would have wanted claims Pandermalis.

They would be very angry.

The ancient Greeks would be very angry?

Yes

Why?

Because they were crazy for perfection. It was a perfection but today it is not.

As for whether he will ever see all the remaining Parthenon Marbles together under this roof.

I'm sure.

You' re sure that you will see them.

But I don't know when.