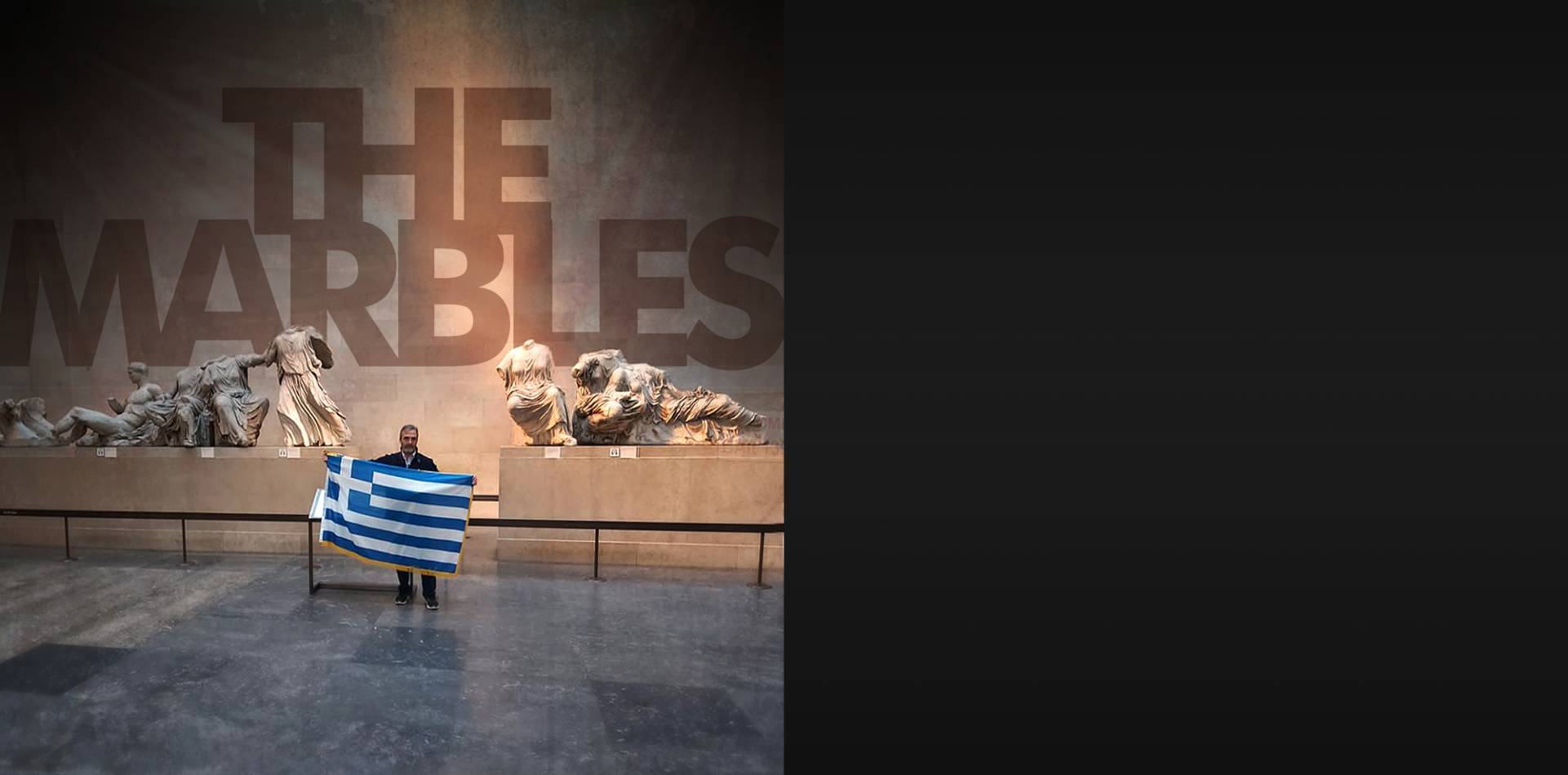

Michelle Pépratx-Evans argues that, beyond the archaeological and aesthetic evidence, the return of the Elgin Marbles is a fundamentally ethical issue.

Preamble

The European crisis, financial in appearance, is in reality profoundly social, even societal. The problems that Greece has faced and those she is made to face are only the tip of the European iceberg. The number, types and levels of dishonourable shameless attacks on the birthplace of our civilisation should remind the thinking public = you, that Aesop’s lesson (the dogs and the fox) “it is easy to kick a man that is down”,13 is sadly relevant to the situation, in particular to the support from Britons, who pay or don’t pay income tax but advise Greece that if they want to stay in the Eurozone, they should accept the consequences and get on with it! Therefore we Europeans need to reflect on the meaning of the word ‘community’ and start building the group that calls itself the “European Community”. This research report on the Parthenon, a perennial issue since the 1816 parliamentary debate, now needs to be made accessible to a wider audience in the hope that the claims which attempt to justify the retention by Britain of goods received from an occupying power are, at last, seen to be what they really are...

Copyright . Michelle Pépratx-Evans

June, 2012

The Parthenon, before its destruction in part by fire during the Venetian siege, had been a temple, a church and a mosque. In each point of view it is an object of regard; it changed its worshippers; but still it was a place of worship thrice sacred to devotion: its violation is a triple sacrilege.4 (G G Byron, 1812)

Download the full article (PDF)

Comments powered by CComment