Monday 15 April 2019, Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Maria Vlazaki, Secretary-General of Ministry of Culture and Sports:

"Honourable organisers and participants; dear guests, colleagues and friends, dear campaigners.With great interest and attention, we watched the speakers' presentations and video messages during today’s Conference held at the Acropolis Museum. Each presentation at today's International Conference for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures was an in-depth approach to the quest to reunite the Parthenon sculptures and each one approached this from a different perspective.

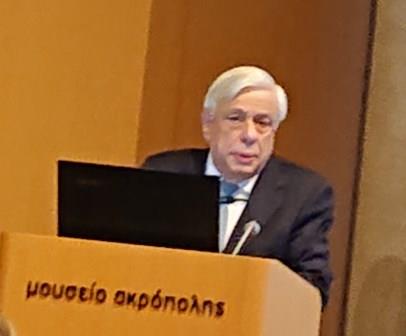

Let us recall the main points of today's speeches: During the inaugural session, the Excellency President of the Hellenic Republic, Mr. Prokopios Pavlopoulos, emphasised that this international conference is yet another link in the long chain of the international struggle for the reunification of this unique cultural collection.He underlined that the fair request for the return of the Sculptures has a long history and began after Greece gained her independence. Moreover, the construction and opening of the Acropolis Museum further weakens the sacrilegious "alibi" of the English side that stated that Greece had no proper place for the sculptures to be exhibited.

(To read the President's full speech, please follow the link here.)

The Minister of Culture and Sports, Ms Myrsini Zorba, stressed that 37 years have passed since the UNESCO Conference in Mexico when Melina Mercouri first formally called for the return of the Sculptures, and referred to their removal as cultural vandalism, an open trauma for the eyes of all humanity.In the decades that followed, Greece and the Ministry of Culture supported, the return of the Sculptures and their reunification in order for the monument to acquire its integrity - a one-way street, a lasting pledge that ‘we’ have a debt to resolve through dialogue.A pending historical, cultural, scientific, aesthetic, political and ethical quest towards the reunification of the Sculptures continues. The Minister congratulated all who helped, promoted and defended the claim, and in particular the national committees.

The President of the Acropolis Museum, Professor Mr. Dimitrios Pantermalis made a very interesting retrospect presentation of the history of the Parthenon monument, presenting in a way particularly characteristic and explaining the ‘adventures’ of three different parts of the sculptures, to their acquisition by the British Museum. He then noted the need to further investigate the Elgin material.

Mr. Christoforos Argyropoulos, President of the Greek Consultative Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, and President of the Melina Merkouri Foundation, argued that in the discourse related to the repatriation of the sculptures from the Parthenon, the Greek side uses real arguments - whereas the British, deliberately and repeatedly use misleading claims.

Mrs. Marianna Vardinoyianni, UNESCO's Goodwill Ambassador, reviewed her actions and initiatives. She referred to both the national and international dimension of the claim, as well as the legal and ethical aspects of the claim, while she also mentioned her aim to continue to gather signatures from prominent international personalities in order to add to the calls for the return the Parthenon Sculptures to Athens.

Former Minister of Culture and Sports, Lydia Koniordou, stressed the Greek side's insistence for a diplomatic path towards the reunification of the Sculptures without forgoing the possibility of using legal action. She too is keen to raise greater awareness of public opinion, which would act as a leverage to persuade the British Museum. Finally, she praised the effective and fruitful collaboration with the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, while observing that the polls continue to also show support for Greece’s legitimate demand.

The second session was followed by the latest developments in the case of the return of the sculptures, coordinated by the Director of the newspaper KATHIMERINI, Mr. Alexis Papakelas.

Professor Bernard Tschumi, architect of the Acropolis Museum, in a brief video message, presented the architecture of the Parthenon friezeand its exhibition at the Acropolis Museum where the visitor can see the sections of the Frieze as they were intended to be seen on the length and breadth of the Parthenon and not like those that hang in the British Museum. He likened the ones in the British Museum as paintings hanging on a wall. The sculptures, he concluded are the living entity of the Athenian democracy.

Academic Eleni Arbeler, President of the European Cultural Centre of Delphi, presented interesting historical aspects of the issue by analysing the conflict between two British scholars and the Sculptures in the late 19th century, and Cavafy's commentary as a journalist - columnist at that time.

Professor Louis Godart, President of the International Association for the Reunion of Parthenon Sculptures, described Italy's actions to combat the illicit trafficking of cultural goods and that his role as a counsellor to the President of the Italian Republic will continue to help him to help Greece in her quest.He appreciated that England is also unable to support the integrity of this symbol of eternal values and aesthetic excellence, especially today where concepts and symbols such as the European Union are shaken and endangered by extreme populist forces. He concluded by saying that the return of the sculptures to the Acropolis Museum would be a move that would honour England and show respect for the whole of Europe.

Actress Dame Janet Suzman, Chair of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, spoke of Melina, public pressure and opinion polls too. She apologised for the mess that the UK found itself at this time because of Brexit. She stressed that timing was everything and that young people no longer appreciate colonial practices and policies. In this context, many museums have and will continue to return cultural artefacts to their countries of origin. She finally suggested that the British Museum would soon be marginalized for its choices, namely to own and expose arts from other countries.

The lifelong scholar of the Monuments of the Rock, Professor of the National Technical University of Athens, Mr. Manolis Korres, presented with great emphasis the basic architectural particularities of the monument, as well as the ideological reports of the overall programme of the construction of the Parthenon’s masonry.

This panels presentations were brought to a close by UK journalist Sarah Baxter, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of The Sunday Times from London. She admitted that England seems to lose the battle in the moral field while expressing the view that the Parthenon Sculptures should be returned to Greece in the same way that the "Coronation Stone" was returned to Scotland.In addition, she expressed the view that the new technologies now make it possible to produce impressive copies of works of art, and that the British Museum could use copies of the Parthenon sculptures and return the authentic ones to Greece.

The third session was dedicated to the discussion of the strategy and the perspectives of the topic, Mr. Nikolaos Stambolidis, Professor of Archaeology, University of Crete, and the Director of the Museum of Cycladic Art, mediated this panel of speakers.

Dr. Tom Flynn, an art historian and writer in his short video message, provided a message for this conference, he expressed the view that public pressure for reunification is increasing, to such an extent that only the "cultural deaf" might not hear it.In addition, he mentioned the 10th anniversary of the Acropolis Museum, stressed that the international museological tendency for smaller museums linked to archaeological sites, while large encyclopaedic museums represent an outdated imperialist concept.

Professor Paul Cartledge, Professor Emeritus of Greek Culture at the Cambridge University School of Classical Studies and Vice President of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, added that the British side's obsession no longer has any legal or moral support in modern day. He spoke of the firman and the Turkish experts that presented in Athens earlier this year. These experts proved that these were but travel permits. In fact no firman would have granted Lord Elgin the right to take down from the building what he did remove.

Dr. Artemis Papathanassiou, Legal Counsellor at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and member of the Greek Consultative Committee for the Reunification of Parthenon Sculptures, highlighted recent developments regarding the return of cultural goods to their countries of origin within the UN and UNESCO, focusing on the emblematic case of the Sculptures of the Parthenon.The most recent development within UNESCO is the adoption of a Recommendation in May 2018 by the Intergovernmental Committee for the Promotion of the Return of Cultural Goods in their countries of origin. In the extremely important recommendation, the Commission first takes into account the historical, cultural, legal and ethical dimensions, while it is recalled that the Acropolis is an emblematic monument of universal scope that has been included in the World Heritage List. In December 2018, the UN Assembly adopted a resolution recognizing the institutional character of the International Conference on Return of Cultural Goods and their final texts, while mentioning once again the request for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures.

Brigadier Fabrizio Parrulli, Commander of the Carabinieri Corps of Antiquities Department, explained that his Department held the world's largest digital database of stolen artworks. He went on to describe the initiative to set up and run the Task Force ‘Unite for Heritage’, which is involved in missions for the protection of cultural heritage in cooperation with local bodies and intergovernmental organisations both within Italy and internationally.He took this opportunity to refer to a similar initiative by the Ministry of Culture and Sport. As early as August 2016, a registry of executives willing to assist businesses to protect the cultural heritage was set up in Italy’s Ministry. Some 51 executives, archaeologists, engineers, conservationists, lawyers, museologists and architects continue to offer their services to international cooperative enterprises under the supervision or invitation of UNESCO or other organisations to record damage, provide know-how and assistance in the protection and recovery of cultural goods.

Professor Emanuel Papi, Director of the Italian Archaeological School of Athens, referred to the long-standing practice of seizing antiquities as early as Roman times, and just before the start of the struggle for the Independence of the Greek State, Greece was the scene of the ‘important monuments of the ancient cosmos’ (Aphaia in Aegina, Epicureus of Apollo, Parthenon). He concluded his speech by asking the Italian State and the Sicilian region to return a piece of the sculpted decor of the Parthenon, which is now in the Museum of Palermo.

Dr. Elena Korka, Honorary Director-General of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, testified the results of the thorough research she conducted in archive material, which reveals both the truth and the fiction that surrounds the removal of the sculpture from the Parthenon, while demonstrating legitimate use by distorting data related to the export of the sculptures by Lord Elgin, and the subsequent acquisition by the British Museum in 1816.

Mrs. Sophia Chiniadou Kambani, Head of Cultural Affairs of the Presidency of the Republic, focused on the erosion of the meaning of the sculptures when viewed away from the context of the monument, and set the goals for the success of the relevant struggle: preventing forgetfulness, the use of diplomatic channel as a main strategy to offer stability and consistency to the campaign, the emergence of the importance of the monument's uniqueness and integrity, as well as the unity and coordination that must identify every initiative, national and international.

The closing session, was co-ordinated by Marlen Taffarello-Godwin, from the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles.

The Deputy Minister of Culture and Sports, Mr. Constantine Stratis, noted that the Parthenon Sculpture case also raises a series of wider issues pertaining to the perceptions of the preservation, restoration, protection and enhancement of the cultural heritage, as well as the way in which it should be presented to the international community. It highlights the problems surrounding antiquity, the property regime, the commercialisation and trafficking of antiquities.Greece has continued to abolish all the arguments of the British side concerning both the preservation and protection of the Sculptures, as well as their appearance and presentation to the public, while the British Museum's rhetoric is rejected internationally as the remnant of an outdated colonial logic.The interventions of the representatives of the National Committees were then heard. They presented with enthusiasm their campaigning thoughts, some also outlined the efforts they have undertaken or implement in their individual countries, contributing to the swell in public opinion for reunification in many parts of the globe. Greece thanks them from the heart! We keep these great ideas and suggestions and we are committed to working on them and making the right use of them.

Professor Ove Bring, a member of the Swedish Parthenon Committee, Professor of International Law, Swedish National Defense College, Stockholm University, former lawyer at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs: proposes that the British Museum obtain exact copies and temporary repatriation of the property. He suggested that ownership is shifted to Greece and that Greece then in turn continues to lend the sculptures to the British Museum.

Emanuel Comino, Founder and President of the International Organization of Organizations (IOC-A-RPM) - supports cultural diplomacy, remarking on how it was Melina Mercouri that encouraged him to work with the British Committee, founded by James Cubitt. He added that the two committees had worked closely together for nearly 40 years and that he would continue to give his personal and committee’s support. He mentioned the International Colloquy held in London in 2012 before the London Olympics, the second held in Sydney, Australia in November 2013 and the third held in Athens in July 2015. He also mentioned attending BCRPM’s 200th commemorative event held at Senate Housewhere Melina Mercouri also spoke, this event was held in London 07 June 2018 to mark 200 years since British Parliament voted to purchase from Lord Elgin his collection of sculpted marbles collected from the Parthenon and elsewhere on the Athenian Acropolis.

George Vardas, Secretary of the International Association (IARPS), Australian Council for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, Secretary of the Greco-Australian Council: analysed the legal dimension of the issue and suggested that the International Court of Justice should be consulted on this matter.

Mrs. Alexandra Pistofidou, Founder and President of the Austrian Committee for the Return of the Parthenon Sculptures, Historian-Palaeographer: presented her Committees use of social media networking as a tool and how these tools might be used to further the campaign of the IARPS.

Professor Maria Guimarães Kangussu, Brazilian Committee for the Reunification of Parthenon Sculptures, Professor of Philosophy, Federal University Ouro Preto: presented the Brazilian activities which included raising students' awareness of the plight of the Sculptures, talked about the website and a photographic exhibition that they will present at their embassy in Athens in November of this year.

Mr Roland Devivier, President of the Belgian Committee, spoke about their new website and facebook page, Mr Pantermalis' lecture in Brussels in January of this year and a Luxembourg decision to set up a committee there too.

Ms Donatella Monterisi Andreani, French Committee for the Return of the Parthenon Marbles, read out a moving letter from Ms Arberler to President Macron requesting the return of the section of the frieze that is currently in the Louvre. The letter also went to the French Ministry of Culture and the Directorate of the Louvre.

Mr Ole Norrback, Finnish Committee for the Restitution of the Parthenon Sculptures, a former Minister and Diplomat, former Ambassador of Finland to Greece, proposed better co-ordination of the actions of national committees in relation to the International Association. He feels there has to be activities on both national and international level.

Ambassador Krister Kumlin, Swedish Parthenon Committee, former Swedish Ambassador to Greece, supported Professor Bring's statement and spoke of the hope that we may get from a young people’s movement.

Professor Dusan Sidjanski, President of the Swiss Committee, Professor of Political Sciences, Geneva University, Honorary President of the Geneva Cultural Centre: talked about cultural diplomacy, but added the need to exert pressure, rather than a judicial claim, and analysed his thoughts on Greek culture and democracy, bringing the value of history and people. Without the will of people the campaign would have no traction.

In summing up, the return of the Sculptures is also directly linked to the theoretical discussions taking place across Europe on the return of so-called "colonial" cultural goods. This is why the current meeting of the IARPS is important not only for Greece but also for the global community. The Greek claim, a timely and imperative demand, is constantly winning supporters at the level of Civil Society and International Organizations. This is confirmed by the recent developments in both the UN plenary session and the UNESCO Intergovernmental Commission, as well as by the presence here at the Acropolis Museum of the International Association and its member Committees.After all, the arguments of the British side have now been broken down one by one:

• Elgin had no legal authority to remove the Sculptures as he did, as modern archival research has also shown.

• A modern Museum operates in direct visual contact with the Holy Rock and the Parthenon.

• New technologies can provide solutions for visitors to the British Museum by creating three-dimensional digital copies of maximum precision.

• The Greek side constantly declares its intention to collaborate creatively with the British Museum, as it has done with other museums, for the presentation of periodical reports and the development of joint research programmes.To achieve our goal, cultural diplomacy and public awareness remain our main weapons. The Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports continues to coordinate and process the necessary steps, updating it on the basis of the data, in cooperation with the National Advisory Committee, the Acropolis Museum and, of course, the Presidency of the Republic.

In the above context, having the International Committees and National Committees working alongside us, we believe that it would not be inconceivable to design and implement a campaign that would take place at the same time internationally through modern technologies and social media tools. On behalf of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, we commit ourselves that the relevant department, the Directorate for Documentation and Protection of Cultural Goods will undertake a public awareness campaign on April 15, 2020, and we call on a similar action on the same day, one year from now. We propose that the Committees discuss the matter at their meeting tomorrow.

We believe that the outcome of this conference is a strong and loud message. In a turbulent period that Europe is experiencing today, the return of the Sculptures from the British Museum will be a gesture of unity and belief in the ideals and values of European culture. As Italy's important institutional representatives are among us, the first step, with the consent of the Italian Government, would be the permanent return of the fragment from the Pietus in Palermo, Italy, and that of the Vatican Museum, with the consensus Holy See. And finally, a larger coordinated effort to return the fragment from the Louvre. Such an achievement would be a decisive precedent for Britain's next moves.

Thank you all.

verage on this, check the articles listed below:

For coverage on the conference, some of the articles are listed below:

Greek president demands UK return Parthenon marbles from ‘murky prison’ of British Museum

Greek president brands British Museum a 'murky prison' for Elgin Marbles

Greece calls on the UK to free the Parthenon marbles from the British Museum's 'murky prison'

Greek president demands UK return Parthenon marbles from British Museum’s 'murky prison'